What we think of as history is sometimes little more than legend or hearsay or speculation – especially when we look back one thousand years or more. A writer of historical fiction must look at legends as well as facts, and must then determine if a given legend can be used in plotting a historical novel. Inventing a scene that incorporates a well-known legend – even if it is suspected to be apocryphal – can add depth to the personality of a historical figure or add perspective to an event. A good example is the story of King Alfred and the Burned Cakes. Bernard Cornwell incorporated this tale into his novel THE PALE HORSEMAN, presenting his readers with the moving portrayal of a young king who has lost all but his name, and who ignores the oatcakes burning on the hearth beside him because he is so intent upon formulating a plan for taking back his kingdom.

Which brings me to a legend about King Cnut. No, not the well known story about Cnut and the waves. This is a legend about Cnut’s daughter, and the setting for it is Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, Sussex.

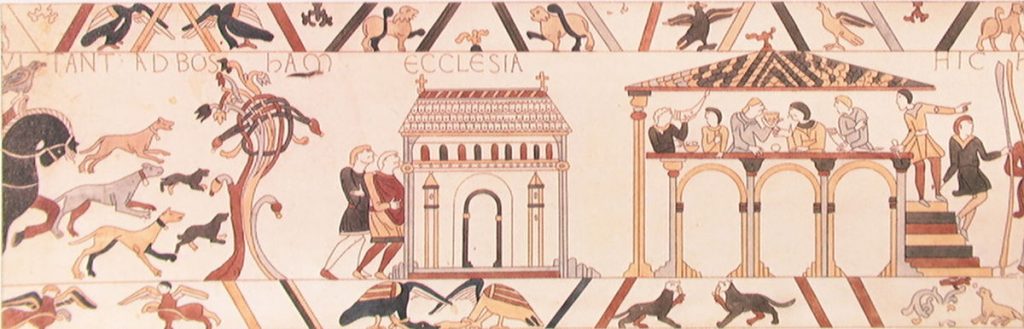

Like many churches in England, Holy Trinity has a long history. In 1064 Harold Godwinson boarded a ship at Bosham and sailed from there to Normandy where he was coerced into swearing fealty to Duke William, setting in motion the events of 1066. We know this, not because it was written in some chronicle, but because the church appears on the Bayeux Tapestry beneath the words: UBI HAROLD DUX ANGLORUM ET SUI MILITES EQUITANT AD BOSHAM ECCLESIA (where Harold, duke of the English, and his knights ride to Bosham church). Historical record comes in many forms!

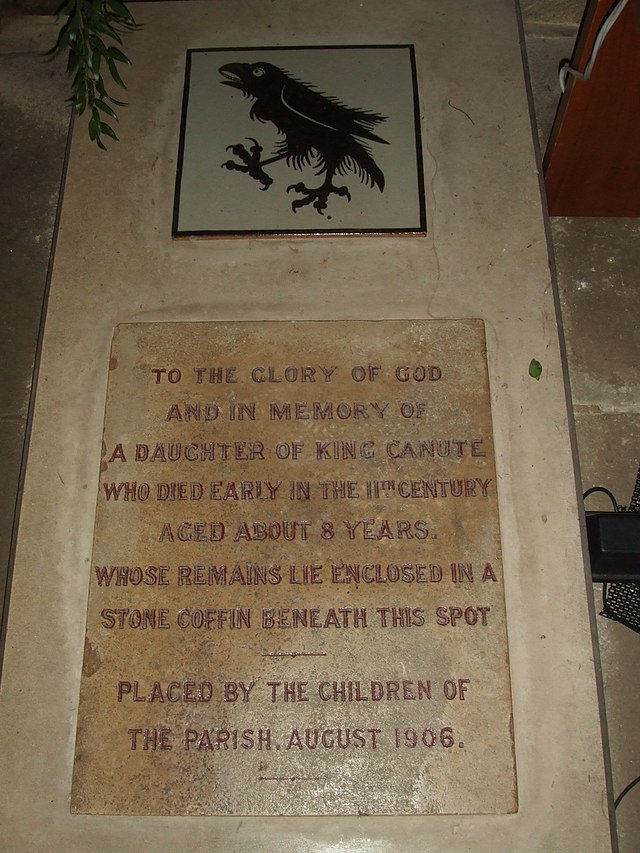

But the legend that interests me dates back even farther. According to a story passed down for a millennium, one of the graves inside Bosham church is that of King Cnut’s 8-year-old daughter who, in the year 1020, drowned nearby. Is there any truth to this story? Well, a coffin has been found beneath the church floor, and it does contain the remains of a child; and because only the elite were buried inside churches, it could very possibly be Cnut’s daughter who rests here.

The legend, though, makes no mention of the girl’s mother, and this is where the novelist in me begins to ask questions and formulate theories:

If this daughter of Cnut was conceived in 1011-12, as she must have been if the dates are correct, where did that happen, and who was her mother?

Surely it was not Emma of Normandy, Cnut’s wife and queen. In 1011-12 Emma was the wife and queen of King Æthelred, not Cnut.

Could it have been Ælfgifu (Elgiva) of Northampton? She was the concubine of Cnut before he married Emma. Historians believe that Cnut’s relationship with Ælfgifu did not begin until 1013, but that assumption is based on the fact that Cnut was known to have been in England in that year. No one knows where he was in the years before 1013, or where Ælfgifu was, or when that handfast marriage (more Danico) was negotiated or consummated. Perhaps the historians are wrong. Perhaps Cnut’s relationship with Ælfgifu began earlier, and she was the mother of this little girl.

There is also a third possibility – a Danish woman named Gytha. In 1019 Gytha married Earl Godwin, and her large brood of children would include the Harold mentioned above who would one day become England’s king. It would also include an eldest son named Swegn, who would claim that he was not sired by Gytha’s husband Godwin, but by King Cnut. Frank Barlow, in his book The Godwins, writes that Gytha vehemently denied this. But he also writes,

Favourable to Swegn’s claim are his possession of a name which ran in the Danish royal family, his constant behavior among the Godwins as an outsider, and his apparent total exclusion from VITA, the family saga. Moreover, if Cnut was indeed Gytha’s lover, the favours he granted Godwin are more understandable.

If Cnut was indeed Gytha’s lover, might their relationship have begun as early as 1011-12 in Denmark? Might Cnut’s young daughter have been a member of her mother’s household when, in 1019, Gytha arrived in England to marry the English Earl Godwin who had extensive landholdings in Sussex including estates at Bosham? Could Gytha and her household have settled at Bosham where, the following year, the little girl would drown in the mill race beside the church?

In searching for answers to these questions, for links between the characters who inhabit my books, for drama, and for smoldering conflicts that will keep readers turning pages, I became a little like King Alfred. Too intent on names and dates and connections, I lost sight of something important. It wasn’t until I stumbled across the lovely poem below that I was jolted out of my feverish preoccupation with names and dates, and was reminded by just a scattering of words that this legend was about a child who had been loved, and whose parents, like all parents throughout time, must have grieved her loss no matter who they were.

CANUTE’S DAUGHTER

By Denise Bennett

Bosham Church

Photo: Hugh Llewelyn (Wikimedia Commons)

There are the expected

candles, flowers, lace-edged altar cloth,

tiled floor, carved pulpit, marble font,

plaque to the war dead…

but buried beneath the Chancel

is the small daughter of King Canute

who slipped and fell into the mill stream

aged eight.

For nearly a thousand years

this memory, carried on our breath

has been told and retold.

Outside, a thick frond of cream roses

are dipping low to taste the flow;

a family of mallards swim in sun;

here the spirit of a girl lingers.

I listen to her laughter, watch the amethyst

light play on the waves her father

tried to tame –

think of him

lifting his dead daughter,

stroking her wet, black hair

cursing that he could not

command the sea.

Sources:

Barlow, Frank. The Godwins. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, UK, 2002

http://www.poetrymagazines.org.uk/magazine/record.asp?id=14790

I’ve seen the Bayeux tapestry but I had no idea Bosham church featured on it – and me a Sussex woman!

The only even near contemporary evidence we have that Harold embarked from Bosham is the Tapestry. Pretty cool, that.

This is a convincing story. And the poem is beautiful.

Thank you for stopping by, Carol. The poem is my favorite thing about this post.

Patricia,

I’ve just finished the first two book in your trilogy. They made history come alive for me and I look forward to the third book being published!

Some of the sites in the books I have been to and will be in additional spots in future trips. Hopefully on our next trip to England we’ll go to Normandy and see the Bayeax tapestry. It was lovely staying at the same B&B with you in Amsterdam. Sincerely, Bernice Rust

Hello Bernice. I’m delighted that you read and liked Emma’s story. Thank you for letting me know. I, too, am hoping to see the Bayeaux Tapestry someday. I haven’t been able to manage it so far, but maybe I can get there after I finish writing Emma’s third book.

I hope you enjoyed the rest of your time in Amsterdam. Our bike/barge trip was great fun, and the weather co-operated, thank goodness!

All best wishes,

Patricia

A fellow Bosham-lover? It’s a lovely little place. Impressed by your forensic approach to the young burial. For possible interest, here’s ABAB’s take http://bitaboutbritain.com/bosham-cnut-the-kings-daughter-and-harold/

Best regards, Mike

Thank you for stopping by! I enjoyed reading your own post about Bosham, and am happy to have discovered your website. I’ll be walking in Northumbria and Yorkshire in the autumn, and will take a look at your website to get some ideas about places to visit while I’m wandering in the north.

For a thousand years, she has rested in both anonymity and fame. Surely someone must know the little girl’s name? God bless her.

Honestly, we don’t even know the name of Cnut’s mother! I’ll be writing a blog post about that soon. If it’s any comfort, in my third novel (not yet published) I’ve given her the name Thyri.