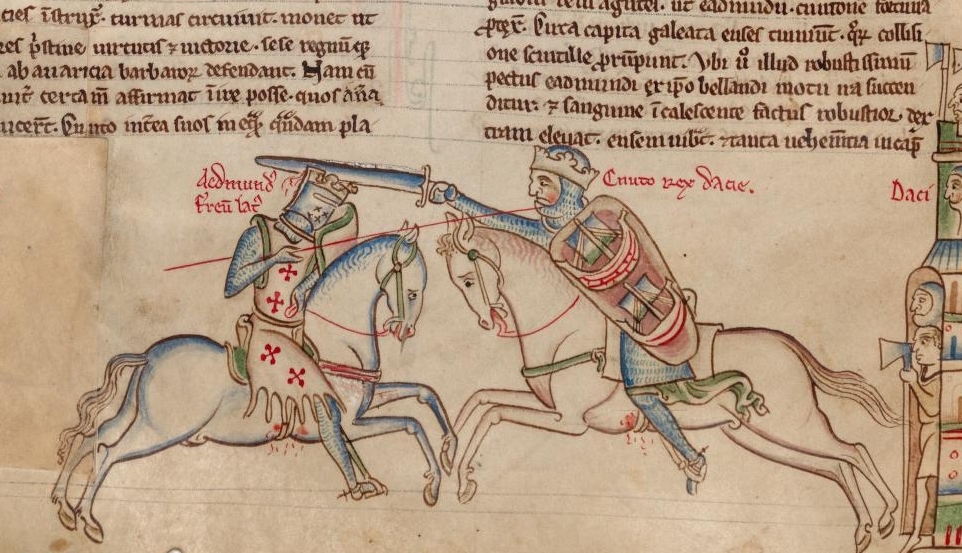

Edmund battles Cnut at Assandun. 14th c, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College (Wikimedia Commons)

And all the nobility of the English nation was there undone!

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

On the 18th day of October in the year 1016 a great battle was fought between the forces of the English king Edmund Ironside and the Danish prince Cnut, younger son of Swein Forkbeard. According to the 12th century chronicler William of Malmesbury, Cnut had sailed to England in 1015 at the head of a massive fleet with the intention of either capturing the English throne or dying in the attempt.

Cnut’s fleet sails to England

Over the course of the next year the two war leaders met in battle four times, with Cnut unable to secure either the decisive victory he so desired or the death that Edmund Ironside would so willingly have granted him. Not until that fateful day in October would the rivalry for the English throne be decided on a down in Essex called Assandun.

Today, the site of that battle is claimed by both Ashingdon in southeast Essex and Ashdon, about 50 miles farther north. In a paper published in 1993, archaeologist Warwick Rodwell carefully considered both sites, but hesitated to definitively state that one or the other was Assandun. Nevertheless, Rodwell’s careful review of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC) account and its tactical implications, along with his boots-on-the-ground research convinced me that the northern site, at Ashdon, is where the battle was fought.

On that October day Edmund Ironside led a force made up of “all the English nation” (ASC) against a Danish army that must have been significantly reduced in numbers after 12 months and 4 major battles. Yet despite the advantage of numbers, the English lost. The 12th century chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote, “On that field Cnut destroyed a kingdom, there the whole flower of our country withered.”

So, how did that happen? The earliest account, the ASC, puts the blame for Edmund’s defeat squarely on the shoulders of the villainous Eadric Streona, who “first began the flight and so betrayed his natural lord”. Eadric had allied with Cnut in 1015 but had deserted him for Edmund when the Danes appeared to be on the losing side in the weeks before this battle. In using the term betrayed, the ASC seems to imply something more sinister than mere cowardice.

100 years later the chronicler John of Worcester went into more detail. He wrote that the English formed a battle line four men deep atop a hill, and King Edmund exhorted them to defend themselves and their kingdom from men that they had beaten before. The Danes approached slowly on level ground, and the English, at Edmund’s signal, attacked down the hill. The battle was fiercely fought on both sides, but Eadric Streona was still secretly Cnut’s ally. So when at Assandun the Danish line wavered and it looked like the English would win, Eadric, keeping a promise he had made to Cnut, fled with all his men “and gave the Danes the victory.”

The battle rages at Assandun

The most extensive account of the battle, though, appears in the Encomium Emmae Reginae, written in about 1043 and therefore earlier than Worcester’s account. In this version, Eadric urged his men to flee even before the battle began! “Let us flee and snatch our lives from imminent death, or else we will fall forthwith, for I know the hardihood of the Danes.” Eadric did this at Cnut’s behest in return for some favor—although the encomiast did not hazard what that favor might have been. Seeing a good chunk of his army leave the field Edmund was undeterred. He told his warriors that they were better off without the craven men who deserted them, and he “advanced into the midst of the enemy, cutting down the Danes on all sides.”

The encomiast claimed that the battle lasted all day—a very long time for a battle in this period—and that although the English had more men, they lost more men, too, than the Danes. It seemed to the English that the Danes were not so much fighting as raging (berserkers?), and that the Danes were determined to die before they would withdraw. When night fell, the English, weary and disheartened, retreated and Cnut was left master of the slaughter field.

It seems clear that whether Eadric Streona fled before the battle began or retreated in the midst of the fray, he betrayed his king and directly impacted the outcome of the battle. Cnut’s collusion with him is somewhat less certain; made even more so by the fact that within a year he executed Eadric ‘most justly’ for his betrayals.

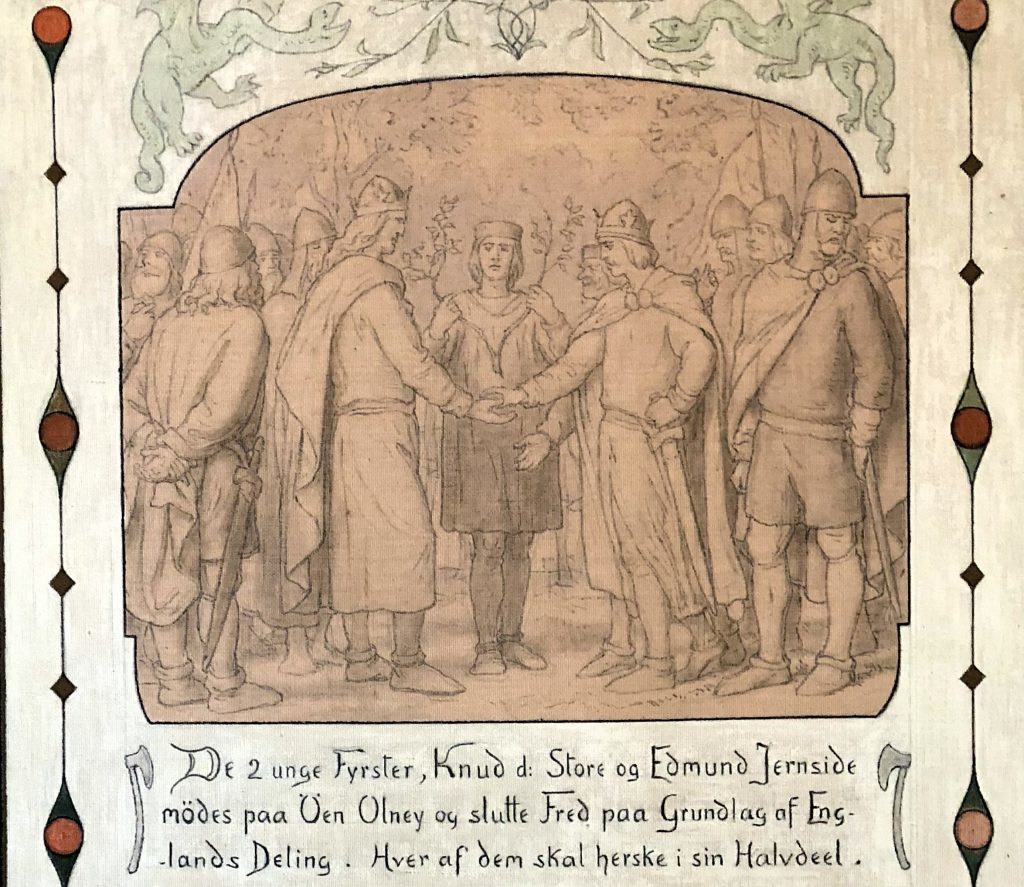

Edmund, apparently not yet willing to concede defeat, fled across England with the remnant of his army to Gloucester, with Cnut on his heels. There, the treacherous Eadric, who had a foot in both camps, brokered a settlement between them that divided England, with Edmund keeping the southern shires of Wessex and Cnut taking Mercia and the north, including the mercantile powerhouse that was London.

Cnut & Edmund Ironside agree to divide England

At this point, according to the Encomium, God stepped in: within a month Edmund was dead, likely from wounds or from an illness he suffered in the aftermath of Assandun. Soon after, Cnut was proclaimed king of England.

The Battle of Assandun, which put a Dane upon the English throne, is not as well known as that other battle that was fought exactly fifty years later at Hastings and resulted in a Norman takeover. There is no Tapestry that depicts the battle of 1016. But in Denmark, in the King’s Corridor of Frederiksborg Castle, both events are commemorated, for both Cnut and William came from Danish stock. On one wall is a hand-painted photographic copy of the Bayeux Tapestry. Facing it is a series of 19th century paintings documenting the 11th century Danish conquest of England, with several depictions of Cnut’s great victory at the Battle of Assandun prominent among them.

Sources:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, trans. Rev. James Ingram, London, 1823

http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/asintro2.html

The History of the English Kings, William of Malmesbury, trans. R.A.B. Mynors, R.M.Thomson, M. Winterbottom, Oxford University Press, 1998

The Battle of Assandun and its Memorial Church, Warwick J. Rodwell; in The Battle of Maldon: Fiction and Fact, Ed. J. Cooper, London: Hambledon, 1993

The Chronicle of John of Worcester, trans J. Bray, P. McGurk, New York, 1995

Paintings: The Danish Conquest of England, Frederiksborg Palace, artist Lorenz Frølich, 1886

Nope, it is Ashingdon in Essex. Canewdon is also Cnut and, nearby, is where he demonstrated to his nobles that he was not a god by failing to turn the tide back

Hi Alan. I’m afraid we’ll have to agree to disagree. I’m persuaded that the site of the battle was the more northerly one, Ashadon. Also, I’m sorry to tell you that modern scholarship is pretty clear that the story about the tides is a total fiction, made up long after Cnut was dead. Which is not to say that Cnut was never at Canewdon; he may well have been.

I’m sure this in Ashingdon Essex.

This has been researched and a superb book by David Snurthwaite(Battlefield of Britain) published in 1984. David was the keeper of Manuscrips at The Army and Navy Museum in London) on the Battle is very well illustrated over a number of pages. Also Moons Farm nearby has found many items from the Battle and also a coin of canute had been found at Ashingdon Minster, built by Canute to celebrate the victory.

Knut possibly went thru Havengore creek into crouch river In 1953 floods the river bank let go and the water flowed to its original line junction between canewdon rd and the Hydewood Lane which would have placed Danish Army at the bottom Assandune hill The Hydewood mentioned in the battle secured Knuts left flank So ASHINGDON in ESSEX is the only POSSIBLE site Why Knut order Minster to built on the remains of Saxon building academia always want change history to suite their thinking Standing on top Ashingdon hill shows its importance During WW2 it was also strong point in case Invasion