Because few of us are doing much in the way of traveling these days, I thought you might like to join me on a virtual visit to London. Not today’s London, of course, but Emma’s London as I’ve imagined it in The Steel Beneath the Silk.

Close your eyes and picture London in your mind, and it probably looks something like this:

Obviously, though, the London of today looks nothing like the London of a thousand years ago. First of all, the 11th century city was a great deal smaller than today’s London, which began life in the 3rd century as a Roman settlement named Londinium. You can see a model of that Roman London today if you visit the church of All Hallows By the Tower and go down into the crypt.

Roman Model at All Hallows by the Tower

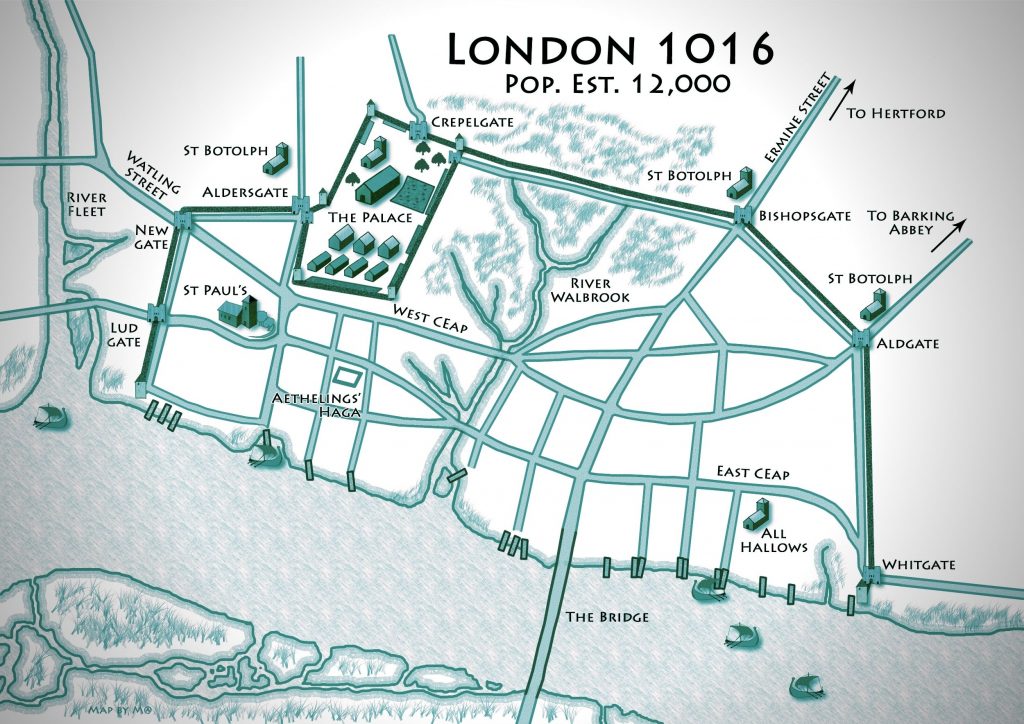

The large enclosed area on the upper left of the model is the Roman fort. Because we do not know for certain where Æthelred’s palace was, but because that northwest corner is one of the possibilities, that’s where I’ve imagined the Anglo-Saxon palace enclosure that Emma would have known.

In 11th century London the royal residence would have been made up of a group of buildings with different functions. The great hall, where the king held court, conducted business, and where the court and the royal household gathered for meals, would have been the largest of them. It may have had chambers recessed into its walls and partitioned off for privacy. There may have been a second story with a gallery on the upper floor where the king could observe the activities below.

Separate buildings—royal quarters—would have been used for more than just sleeping. Emma may have had her own building in the complex, and it would have been divided into rooms earmarked for different purposes. The children would have grown up there, cared for by nurses and tutors. It might have been a place of refuge for the women of the court if things got too rowdy in the hall. Other buildings in the magnificent, urban palace complex of London might have included guest houses, kitchens, stables, a chapel, weaving sheds, a forge, an armory, and a barracks. I’ve imagined a garden and even an orchard inside the palace walls.

In 1016 London itself was still surrounded by that defensive wall built by the Romans. It was nearly 10 feet wide at the base and 20 feet tall. Bits of it still exist in London today, conveniently located on a street named London Wall near the Museum of London.

Bastion of London’s Wall

You can get up close and personal with London’s wall, and even follow a London Wall Walk that follows the line of the wall for almost 2 miles from the Tower of London to the Museum of London.

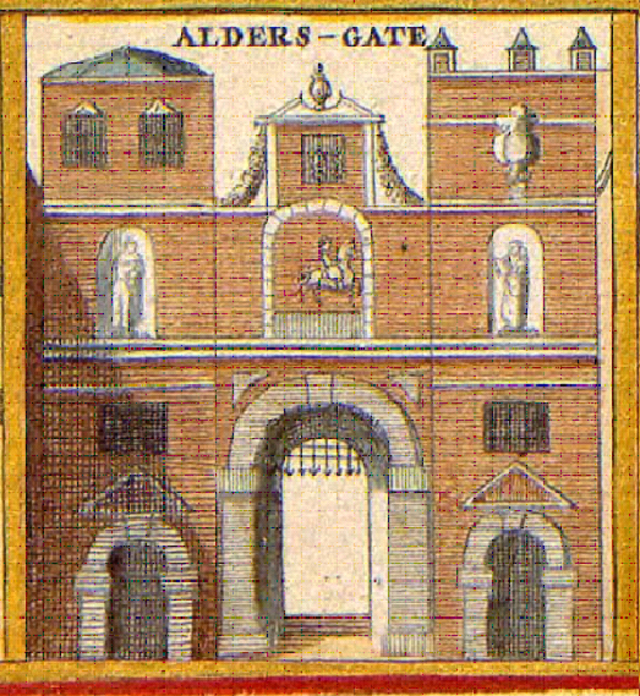

The seven Roman gates that led into the city were still there in the 11th century and well beyond. Below is a drawing of the Aldersgate, one of three gates on the city’s northern border. The Aldersgate is the setting for a tense scene in The Steel Beneath the Silk, with its two-story towers on either side of the gates. Those gates would have been closed at sundown and opened again at sunrise.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

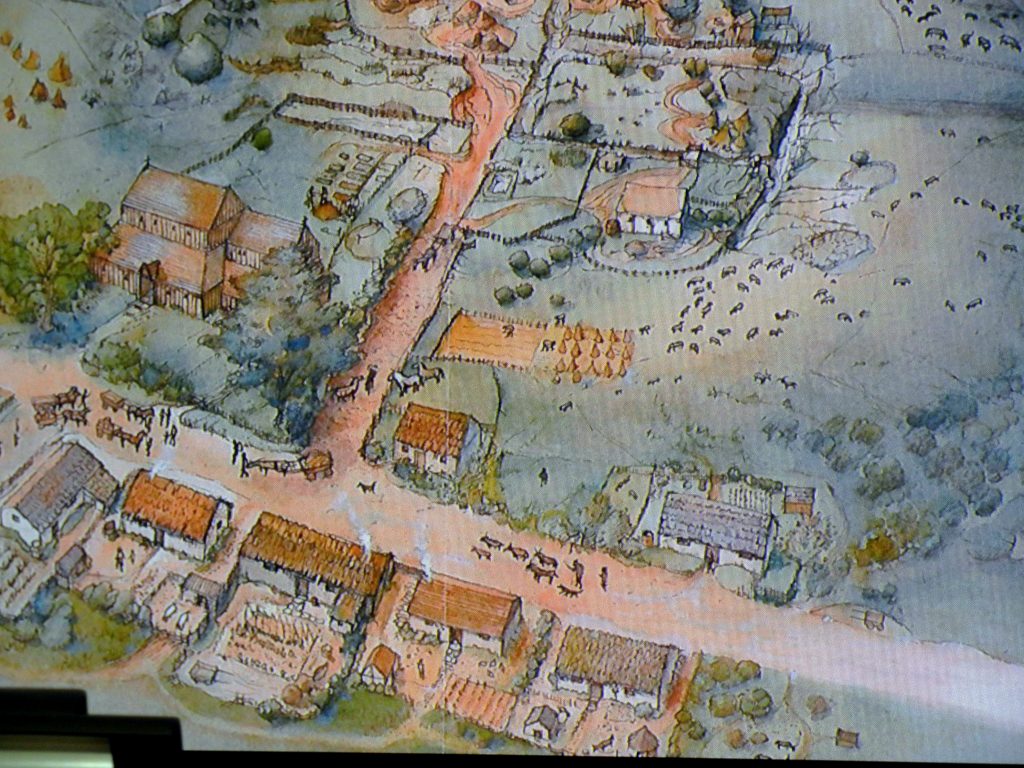

There was empty moorland north of the city, just outside the walls, and inside the walls there was plenty of empty space as well. Andrew Reynolds (University College London Institute of Archaeology) speaking at a conference to commemorate the Siege of London in 1016, showed a couple of drawings that imagined 11th century London. One of them emphasized the pastoral aspect of some parts of the city.

London 11th c, Andrew Reynolds (University College London Institute of Archaeology)

Note the two-story church; the thatched houses with their vegetable gardens, the dirt streets, the cattle, the hay ricks, and wheat fields. (There were actually vineyards in London in the 11th century. I cannot speak to the quality of the wine.) Although London probably had a population somewhere between 12,000 and 16,000, it was fairly rural in the northern and eastern areas of the city where fewer people lived.

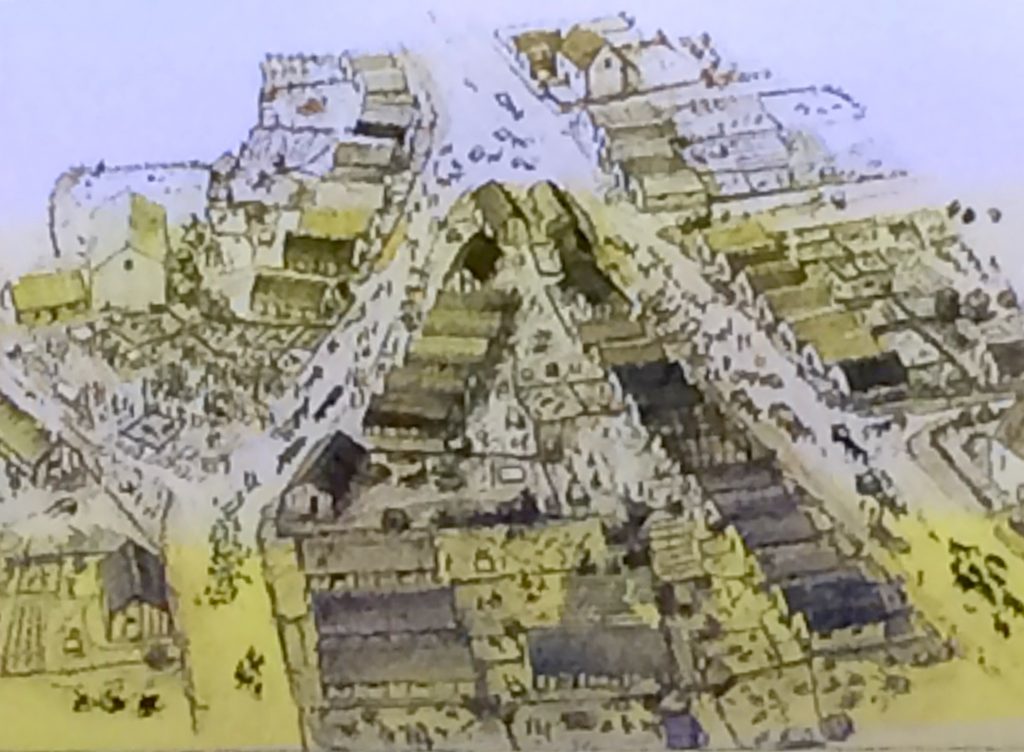

The lecturer’s second image, though, was of an area more densely settled, closer to the Thames.

London 11th c, Andrew Reynolds (University College London Institute of Archaeology)

The houses are packed closely together, but each dwelling has a garden in behind. These drawings were based on archaeological digs at these sites in the city.

There were many churches in London as well as just outside the city walls. The map below, drawn by Matt Brown for The Steel Beneath the Silk, shows several of them. Churches dedicated to St. Botolph, the patron saint of travelers, stood outside Aldgate, Bishopsgate and Aldersgate.

Not shown on the map, but just outside the gate near St. Paul’s was St. Bride’s church, dating back to the 6th century. It’s still there today, and visitors who go down into the crypt can see the remains of the Anglo-Saxon church and a strip of Roman pavement.

St. Paul’s cathedral was made of stone, and there was a wide swath of open area on its eastern end where the Londoners would gather to hear royal proclamations, to learn of the death of a king, and to choose by acclamation his successor. That open ground plays a slightly different role in my new novel, but you’re going to have to read the book to find out what it is.

All Hallows By the Tower, which I mentioned earlier, stood on the eastern end of the city not far from the Thames. It is still there today, although much of it was destroyed in WWII. In the midst of the rebuilding a wall was discovered that dates back to the Anglo-Saxon period.

The church was not called All Hallows By the Tower originally because there was no Tower until after the Norman Conquest. But according to Peter Ackroyd in London, The Biography, on the hill where the Tower now stands—known as the White Mound—was a giant Saxon cross, probably visible from most of the city.

It takes a lot of imagination to recreate in one’s mind what a place might have looked like a thousand years ago. My house in Oakland, California, for example, was a cow pasture in 1910. What it looked like 900 years before that is anybody’s guess. Maps are an enormous help, though. The earliest map of London that I’ve found dates to 1270, well beyond the Anglo-Saxon period. But along with my visits to London’s museums and the work of academics and archaeologists like Professor Reynolds, it is the template on which I built the London that Emma might have known.

Very interesting and detailed summary of 11th C. London; thank you for posting! My wife and I are planning our first trip to England (delayed due to covid, unfortunately), so I am thrilled to find more & more info like this.

I’ll be putting in an order for your first book, Shadow on the Crown, later today. It sounds like a fascinating story, set in a time period that I’ve always found of interest. Thanks again!

Hi Steve. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. Thank you for leaving a comment. I hope you make it to England soon. I’m hoping to get there myself next year, if not this year. I am eager to re-visit Winchester, this time to see the exhibit Kings & Scribes: The Birth of a Nation Exhibit at the cathedral. Plaster replicas of the bones of Emma of Normandy are on display while the actual bones, along with those of other royals buried in the cathedral, are undergoing examination. Someone just recommended on Facebook Rory Naismith’s book ‘Citadel of the Saxons’, which covers London’s history from the late Roman period to 1100. I’ve not yet read it, but I’m planning on it. I hope you enjoy Shadow on the Crown.

This is fascinating… I wish it was still called Londinium, it’s such a brilliant name and it sounds so much more adventurous to say, “I’m going to visit my brother in Londinium…”

Hi Hilary. Hmmm. Well, Londinium is a bit of a mouthful. My Oxford Dictionary of Place Names suggests that it may be derived from 2 pre-Celtic roots with added Celtic suffixes describing a location on the lower course of the Thames (below its lowest fordable point at Westminster), with a meaning something like ‘place at the navigable or unfordable river.’ Which is also a mouthful. But yes, a visit to Londinium does sound like an adventure!

I love all these word origins and place names…not long to go now before I can set aside 2 days of reading and drinking tea… ☕?

Your post reminded me of my last trip to London in 2019 when I researched the same thing. I found the exhibit of the Roman era at the London Museum interesting and from there, walked the remainder of the Roman Wall. It’s fun to imagine and recreate another world based on the archeology and especially to walk along the old passageways and try to sense what my characters’ saw or smelled during their time.

Hi Angela. Yes, walking those passageways and trying to imagine the past is exhilerating. (Londoners must think we’re nuts.) The Roman exhibits at the London Museum are fabulous. I kept wishing they had more on the Anglo-Saxons, though. Nevertheless, one of the curators was immensely helpful when I contacted her about possible sites of the Anglo-Saxon palace.

What a brilliant post, really letting us see how you imagine the 3D setting for your world. Thanks for posting! I love how so many different layers peek out of London’s fabric, and can’t wait to return as well.(My favorite things to spot are Victorian industrial flourishes and Arts and Crafts protests ;D)

Hello Margaret.

Yes, lots of layers in London. The Victorians are a bit easier to find than the Anglo-Saxons. :)