In Chapter Two of The Steel Beneath the Silk King Æthelred asks his son Athelstan why he has arrived several days late to an important meeting of the witan. Athelstan responds, “I was in Devon, my lord, responding to news of viking raids there, and to a report that they appeared to be making for the Severn.”

One of my readers was puzzled by the fact that I did not capitalize the term ‘viking’ throughout the entire book. He was used to seeing the word printed this way: Viking. And it is true that when one types ‘viking’ in a WORD document, the auto-correct insists that it should be ‘Viking’. In my first two novels the word ‘viking’, whether singular and plural, was capitalized. So why did I go out of my way to do something different this time around?

Actually, one of the first questions my editor posed as we were preparing this manuscript for publication was, “Should it be Viking or viking?” No one had ever asked me that before. With the first two novels we had simply acquiesced to WORD’s opinion, but this time around I gave it some thought.

Historians are not in agreement on this subject. For example, in Frank Stenton’s definitive work Anglo-Saxon England (1943, 1971, 1989, 1998, 2001); in Timothy Bolton’s Cnut the Great (2007); and in Levi Roach’s Æthelred the Unready (2016) the word ‘viking’ is not capitalized. In Peter Sawyer’s Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (1997, 1999, 2001); in Ann Williams Æthelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King (2003); and in Ryan Lavelle’s Æthelred II: King of the English 978-1016 (2002, 2004) it appears as ‘Viking’. We seem to have something of a stalemate. What’s a historical novelist to do?

I don’t know when the term ‘the Viking Age’ (always capitalized) was first coined, but surely it was long after these men were actually roaming the seas and plundering Europe. The Oxford English Dictionary has a quote from P.B.DuChaillu in 1889 that reads “We must come to the conclusion that the ‘Viking Age’ lasted from about the second century of our era to about the middle of the twelfth,” thus indicating the first use of that term at the end of the 19th century. (Today’s scholars would disagree with DuChaillu’s opinion that the Viking Age began as far back as the second century!)

And here we have another vote for Viking!

At any rate, to resolve the issue I turned to the first mention that I could find of the word viking, which was the Latin text of Archbishop Wulfstan’s ‘Sermon of the Wolf’. Wulfstan delivered his sermon in 1014, and he used the word ‘wĪcinge’. There was no capital letter. Because my novel was in the same period in which Wulfstan lived, and because I wanted to get inside the heads of my characters, I decided that, this time around, I would follow Wulfstan’s lead.

In my mind, the vikings—no capital letter—are, as Sawyer defines them, ‘roaming fleets of seaborne heathen’; while the Vikings—capitalized—are a Minnesota football team.

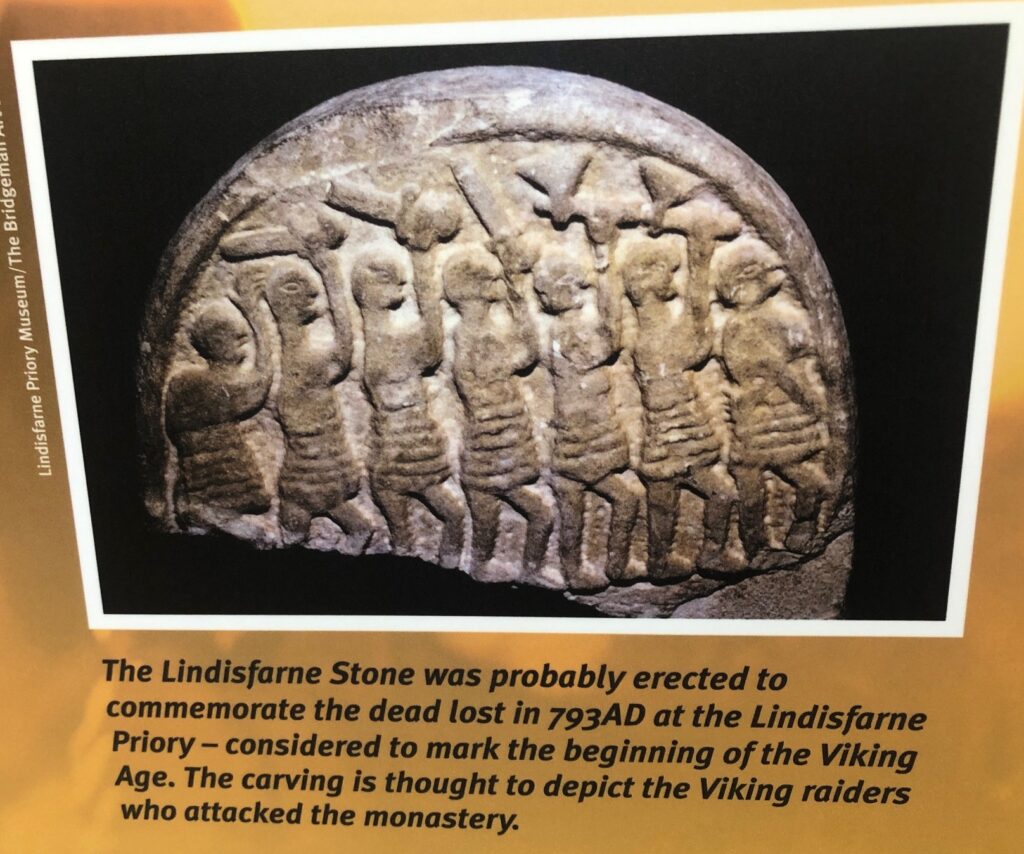

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If you’ve made it all the way through this explanation without your eyes glazing over, congratulations and thank you! Feel free to weigh in via the Comments.

viking or Viking:

If I am using viking as a noun, I capitalize it.

If I am using viking as a verb (ie: to go out a viking as in raiding), I use lower case.

Humphrey Bogart vs to bogart a joint.

Best regards,

Brian

Fair enough, Brian. That’s an interesting way to look at it. And thank you for introducing me to the verb ‘bogart’ which I’ve never heard before. (I lead a sheltered life, apparently.)

Anglo-Saxons didn’t tend to use capital letters at all in their writing.