King Harold I. 13th century. British Library. (Wikimedia Commons) That rabbit looks nervous.

The first king of England to be named Harold (there would be a second Harold, whose reign was even more brief but who is far more famous) died on March 17, 1040 at the age of about 25. His by-name, which has stayed with him to this day, was Harold Harefoot.

Harold was the son of the Danish King Cnut and his English concubine Ælfgyfu of Northampton. His parents’ union took place in England some years before Cnut captured the English throne in 1016. Harold was their second son, probably born in Denmark in about 1015.

Harold earned his by-name by scooting from somewhere in northern England to Oxford quick-like-a-bunny to present himself to the witan soon after his father died at Shaftesbury in November, 1035. Claiming that he was Cnut’s son, and presumably with his mum at his side to certify it, he demanded to be designated king of England as his father’s heir. His claim, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was incredible to many, but the Chronicle doesn’t say why. Was it incredible because he had never been seen at court so no one knew of his existence? Was it because he had never been given any responsibilities by his father and so was considered inept? After all, his older brother (Swein, who died at about this time) had been sent to rule Norway, and his younger half-brother was king in Denmark. Or was it incredible because many people believed the story that he wasn’t really Cnut’s son, but the child of a servant that Ælfgyfu had passed off as hers and Cnut’s? In fact, there were three other men who could have claimed the English throne at Cnut’s unexpected death, but Harold was the only (presumed) son of a king in England at the time. Harefoot got there first.

The man that the witan wanted to put on the English throne was Cnut’s son by Queen Emma, Harthacnut. But he was in Denmark fighting off a Norse army and couldn’t get to England to stake his claim; it was obvious to the witan that he might be a while and that someone had to govern until he arrived. Queen Emma and her close supporter, the powerful earl Godwin, offered themselves as regents for the absent Harthacnut. But Harald had allies who argued against that. Some of them were likely his mother’s northern kin. Others were northerners who were Godwin’s rivals and who considered Godwin already too powerful. The leaders of Cnut’s fleet, too, argued for Harold. Historian N.J.Higham suggests that they might not have wanted to see a Dane land in England with his own fleet that would put them out of business.

In the end, a compromise was reached: Harold would “hold” England for himself and his brother. Queen Emma, with Godwin’s support, would “hold” Wessex for Harthacnut. What must have stuck in Harold’s craw was that Emma, in Winchester, also “held” the royal treasure.

According to Emma’s Encomium—an account of events written at her behest about six years later—Harold wasn’t happy just ruling in the north. He wanted all of England (and, no doubt, Cnut’s treasure.) He summoned the Archbishop of Canterbury and demanded to be crowned. The archbishop refused to do it as long as Emma’s sons lived. He put the crown and the scepter on the altar (in Canterbury, presumably) and forbid any bishops to remove them or to consecrate Harold. Unable to act openly against Emma, in the months that followed Harold used bribes and threats to secure the allegiance of the great men of England. One of them may have been Godwin because he was deeply implicated in what happened next, involving the other claimants to the English throne, Emma’s sons by her first husband, King Æthelred.

Back in 1016 when Cnut conquered England and married their widowed mother, Edward and Alfred had been sent to their uncle’s court in Normandy.

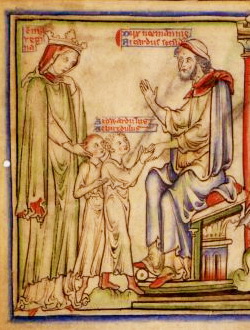

Queen Emma entrusts her sons to her brother, the Duke of Normandy. The Life of Edward the Confessor. Cambridge. (Wikimedia Commons)

They were still in Normandy in 1036 when Harold was ruling in London, Emma was in Winchester waiting impatiently for Harthacnut, and historical events began to get historically murky.

According to the Encomium, Harold had a letter sent to Emma’s sons, supposedly from Emma, entreating one of them to come to her “speedily and privately” to consult with her about what they were going to do about Harold the usurper. Most historians agree that the claim of the Encomiast—and therefore Emma—that the letter was forged, was a lie. They believe that Emma, desperate to maintain her position as queen despite Harold’s growing support—either summoned her sons or sent them some information that encouraged them to make their way to England. Even Emma’s biographer Pauline Stafford believes that Emma sent that letter and that “her appeal to them was at best sanguine, possibly self-deluding and at worst politically immoral.” I’m inclined to believe Emma’s claim that Harold actually sent them a letter or that they came on their own, lured by the knowledge that mummy was sitting on a vast treasure. (But what do I know? I’m a novelist, not a historian. And I’m prejudiced toward believing the queen.)

In any case, they came. Edward (age 30) sailed to Southampton, took one look at the bristling army waiting to meet him, and turned straight around and sailed back to Normandy. Alfred (age 24) sailed from Flanders and when he made landfall was met by Godwin, his mother’s supporter, someone he could trust. Godwin, though, was already following orders from King Harold. We know this because he would claim it in his defense some years later when he was tried for his involvement in this affair. He delivered Alfred and his company to King Harold’s men who proceeded to brutally murder most of Alfred’s companions. Alfred was taken to Ely where he was given some form of trial, blinded and then murdered.

There is an aspect of Alfred’s death that I have not seen mentioned anywhere in my research, and I am surprised by its absence. King Harold had two uncles–his mother’s brothers—who were blinded by Alfred’s father, King Aethelred. In that same year Harold’s grandfather, Ælfhelm, was murdered on Æthelred’s orders. It is hard for me not to see the vengeful hand of Harold’s mother in the blinding and murder of Alfred. And with an unmarried Harold sitting on England’s throne, the queen at his side, counseling him, would be his mother, Ælfgyfu, eager for a long-awaited revenge.

In 1037, Harold moved against Emma. As the mother of Alfred, who had been tried and executed for attempting to unseat King Harold, she would have been implicated (because of that letter) and so she was driven out of England—in the winter, we’re told, so probably in January or February. Harald finally got his hands on Cnut’s treasure! (What reward did Godwin get, I wonder.) Harold was now king of all England. Perhaps he was even crowned, but his reign was short—four years and sixteen weeks, dating from the death of his father. His only recorded act, aside from the murder of Alfred, was to send troops to punish the Welsh for border raiding. The Welsh responded by pummeling the English, which did nothing for King Harold’s reputation.

Harold Harefoot. 14th c. British Library. (Wikimedia Commons) Note crown & scepter. Bunny looks happy.

By the end of 1039 King Harold might have been ailing, although from what, it is impossible to know. (It’s interesting that all of Cnut’s sons died of natural causes in their mid-twenties, and that Cnut’s brother died young as well. Some genetic weakness?) Harthacnut had resolved his problems in Denmark and by early 1040 had raised a fleet and sailed to Bruges to consult with Emma, prepared to invade England. When Harold died on March 17, 1040, English emissaries went to Bruges and offered the throne to Harthacnut. One of his first acts as king was to disinter his half-brother’s body, behead it, and toss it into a fen—vengeance taken on one half-brother for the murder of another, Alfred.

Sources:

Stafford, Pauline. Queen Emma & Queen Edith: Queenship and Women’s Power in Eleventh-Century England. 2001

Howard, Ian. Harthacnut: The Last Danish King of England. 2008

Higham, N.J. The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. 2000

Campbell, Alistair. Ed. Encomium Emmae Reginae. 1998

Savage, Anne. Trans. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. 1984

This was incredibly interesting, a part of history I knew nothing about. Thanks.

In Viking/Danish tradition, princes were often traded to other powerful families to be raised. For example Harold I’s ‘father’ Cnut had been put in the care of Thorkell “The Tall” as a young man. It was Thorkell that led the Norman Jomsviking invasion of England which put Cnut in power in 1016, for which Cnut named him Earl of East Anglia. Interestingly, Thorkell had a son named Harald Thorkelsson (1015-1040) – literally the “son of Thorkell”, and near the end of his life in the 1020’s it is written that Thorkell and Cnut ‘traded sons’ after patching up a dispute. If the same person, this would make Harold I an honest family member of the Danish monarchy (down the line of Gorm – Sigvaldi – StrutHarald – Thorkell), but also explains why there were concerns about illegitimacy, the icy relations with Cnut wife and even why he didn’t share the genetic issues with his two ‘brothers’. He wasn’t a bastard – he was most likely a nephew keeping a secret.

Wow! If I understand you, you are saying that Harald Harefoot was not Cnut’s son, but Thorkell’s. Do I have that right? I’m very curious to know if that is your own theory, or if you have seen some scholarship on that. It’s certainly new to me, and quite intriguing. I’ve seen references to Cnut having been fostered by Thorkell; I’ve read, too, that Thorkell and Cnut exchanged sons in the 1020’s. After that Thorkell fades from the histories, at least according to my sources. But nothing is ever said about that boy who was handed over to Cnut. Huh. But that raises the question: did Aelfgifu actually have 2 sons, Swein and Harald, or only one? thank you for giving me something to puzzle over!

The Spanish Wikipedia, translated by Google, has this to say about Harald Thorkildsson:

Harald Thorkildsson (Danish: Thorkildsen, d. 1042), was a Viking chieftain and jarl of Denmark under the reign of Cnut the Great in the 11th century. He accompanied Cnut’s teenage son, Sveinn Knútsson, who took the Norwegian throne on the death of Olaf II the Saint and acted as co-regent of Norway alongside Sveinn’s mother, Ælfgifu of Northampton. He participated as commander of the Danish fleet in the battle of Soknasund against the claimant to the Norwegian crown Tryggve whom he defeated.

He married in 1031 Gunhild Burislawsdatter (986 – 1066), daughter of King Burislav of the Wends and Tyra Haraldsdatter. From this union they would have two sons, Thorkild and Hemming, both princes of Holstein. Harald was the son of Thorkell the Tall, and by that marriage he was a claimant to the Danish crown. He died fighting on the battlefield against Ordulf, son of Duke Bernard of Saxony, on November 13, 1042.

Interestingly, another source says Harald was born 1015, which would make hium just 16 when he married Gunhild, who was 45 at the time.