Have you ever wondered where an author’s ideas come from? How they develop from an image or idea and grow into story? My guest today, historical mystery novelist Candace Robb, is about to enlighten you.

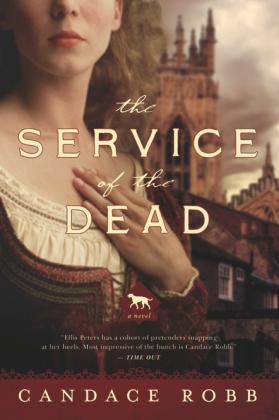

Candace Robb is the bestselling author of 14 crime novels set in 14th century England, Wales, and Scotland, including the acclaimed Owen Archer series and the Margaret Kerr trilogy. Writing as Emma Campion, Candace has published historical novels about Alice Perrers and Joan of Kent. Now she has begun a new historical mystery series built around her heroine Kate Clifford, a no-nonsense sleuth who is not only smart, but fierce when those she cares about are threatened. In this post Candace reveals how she first imagined Kate, and gives us a glimpse into her own complicated mental process as she invents characters, setting, theme and, ultimately, the blueprint for a mystery.

Candace Robb is the bestselling author of 14 crime novels set in 14th century England, Wales, and Scotland, including the acclaimed Owen Archer series and the Margaret Kerr trilogy. Writing as Emma Campion, Candace has published historical novels about Alice Perrers and Joan of Kent. Now she has begun a new historical mystery series built around her heroine Kate Clifford, a no-nonsense sleuth who is not only smart, but fierce when those she cares about are threatened. In this post Candace reveals how she first imagined Kate, and gives us a glimpse into her own complicated mental process as she invents characters, setting, theme and, ultimately, the blueprint for a mystery.

WHENCE KATE CLIFFORD: CONSTRUCTING THE SCAFFOLDING FOR A HISTORICAL CRIME SERIES

I discarded my original title for this post because I’d veered off in a different direction. Yet in rereading it, I thought it nicely described the seed from which the Kate Clifford mysteries grew, so I offer you—Kate Clifford and the Feuding Royal Cousins: the city of York’s response to the fall of Richard II and the Rise of Henry IV.

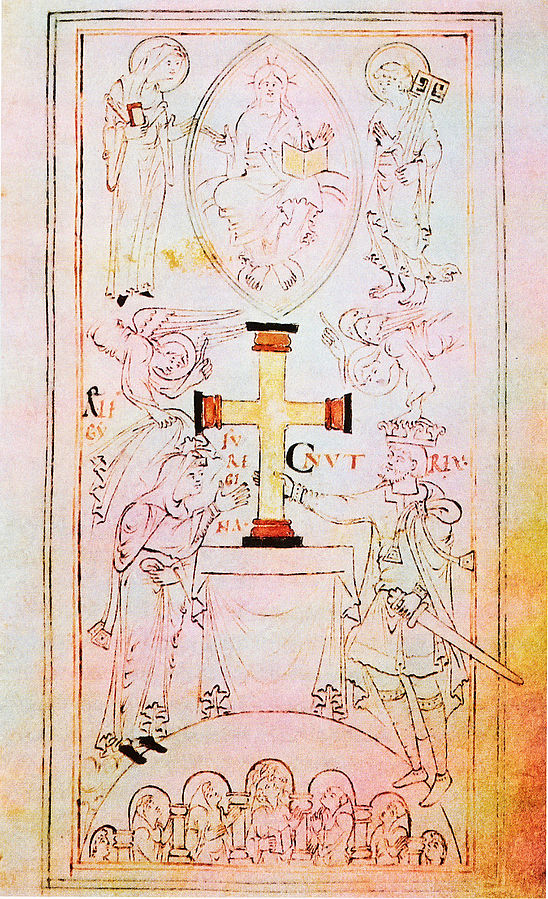

This will be a continual thread through the books, though of course the series will explore much, much more. Which is why my fascination with the fall of Joan of Kent’s son and the ensuing reign of King Henry IV shaped itself into a crime series rather than a historical novel, or a trilogy: I wanted the freedom to send out shoots in many directions. York stands in for the realm at a time of monumental change—King Richard II was the holy anointed king, so to those who believed in the divine right of kings, Henry Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the throne, however enthusiastically received by the barons of England, would have felt apocalyptic. Henry IV’s reign, in turn, would be fraught with bloody uprisings as many came to regret their support.

But whence Kate Clifford? After working with Alice Perrers and Joan of Kent, two strong women, although constrained by the gilded cage of the royal court, I wanted to return to my earlier work with women of the rising merchant class. Women of this class could enjoy far more independence than women of the royal court. Using situations I had come across in my research, I thought to create a 15th century woman of the merchant class intent on forging her own path, and show how that might be accomplished, albeit with some difficulty.

But whence Kate Clifford? After working with Alice Perrers and Joan of Kent, two strong women, although constrained by the gilded cage of the royal court, I wanted to return to my earlier work with women of the rising merchant class. Women of this class could enjoy far more independence than women of the royal court. Using situations I had come across in my research, I thought to create a 15th century woman of the merchant class intent on forging her own path, and show how that might be accomplished, albeit with some difficulty.

Implicit in this idea is a woman at a crossroads, someone who already has a modicum of freedom. In 1399, she might be a widow. A young widow in York. That married my two ideas: both Kate and the realm at a crossroads.

In late August a few years past, a young woman with dark, curly hair strode into my daydream—rather, she was striding down Stonegate (York) with a devilish glint in her eyes, flanked by two magnificent Irish wolfhounds.

Inspirational wolfhounds in Candace’s neighborhood.

I liked her, but the wolfhounds—the tallest of dogs, at this time often used as war dogs—why did she keep them in a city? Was she visiting from the countryside? She patted something hidden in her skirts. An axe. A small battle axe. She turned left onto High Petergate, she and the hounds moving as a unit, then entered an elegant house, where she was greeted with respect as “Mistress” by an elderly couple though they, too, seemed of the merchant class. This was not her home, though she owned this property. A guesthouse?

About this time I was reading the biographies of members of parliament for York 1383-1421 (www.historyofparliament.org). This intriguing woman might be a member of any one of the many wealthy, influential, powerful families in York who served as MPs. Was she a Holme? A Graa? A Frost? William Frost was a figure I found particularly appealing—many times mayor of York, an opportunist easily adapting to the new royal regime though he had worked closely with King Richard II for the sake of the city’s charter. Reading between the lines, he was a man with many enemies, perfect for a recurring character in a crime series. William was too young to be my sleuth’s father, but he’d work well as a cousin. However, the Frost family did not seem likely to be the source of a young woman who moved about with Irish wolfhounds and hid battle axes, no matter how small, in her skirts. Her mother might be a Frost, married into a family in a wilder area, where she had raised her children.

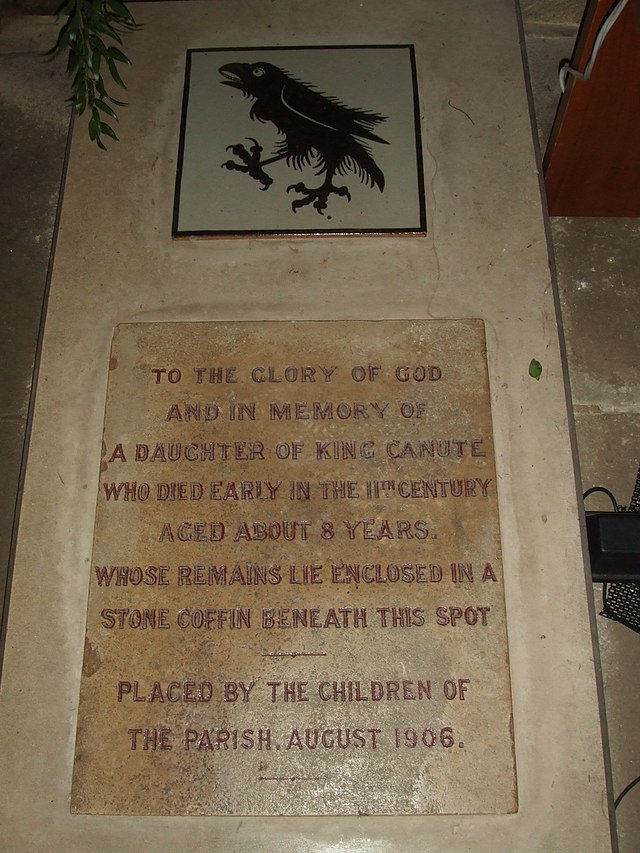

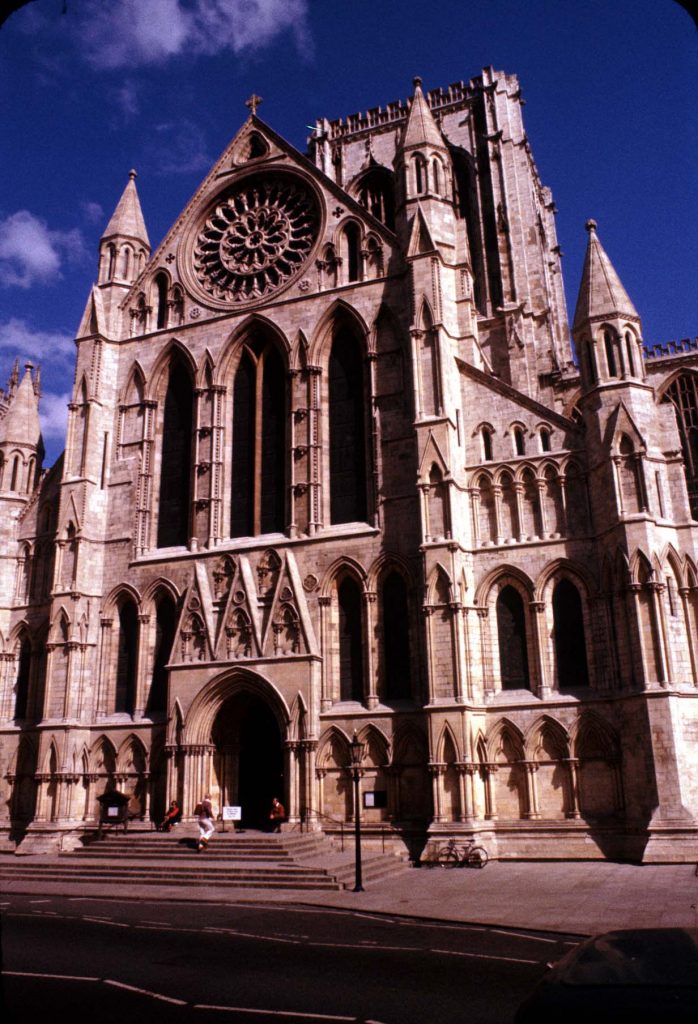

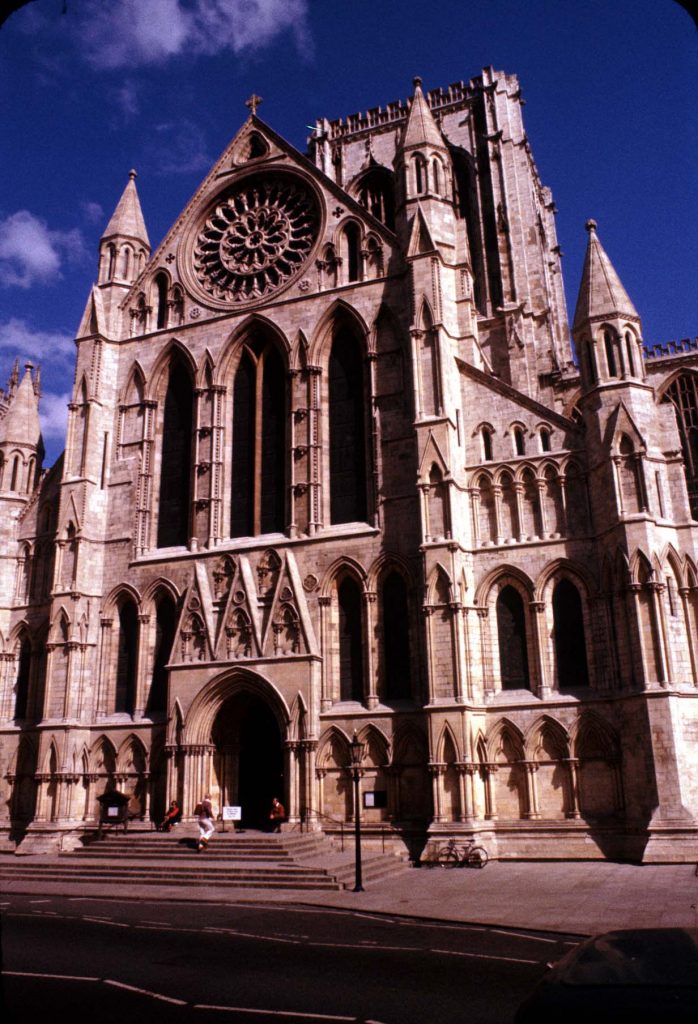

York Minster

The Cliffords were a family of the northern border with Scotland, and Richard Clifford happened to be Dean of York Minster in 1399 (and Lord Privy Seal). Father a Clifford, mother a Frost—an excellent pedigree. Now what could I add to make my character even more likely to get caught up in politics in York? Ah—her late husband might be a Neville. The Nevilles had a presence at Sheriff Hutton Castle in the Forest of Galtres just north of York, and Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmoreland, was one of the greatest opportunists of the time. Perfect.

But why is she still walking around armed in the city of York, and why is she so determined to remain single even though she so wants children? Look to her late husband’s will. Wills are invaluable testaments to relationships and values. The ones that most intrigue me are those in which the dead seek to control their families from the grave with conditional gifts—I bequeath this to you on the condition that you do not remarry, or that you marry X, or until such time as our son attains his majority, or until such time as you remarry. By now my sleuth had a name, Kate Clifford—she preferred her family name to that of her late husband. And now she was the victim of just such a conditional will—that she would control her late husband’s business so long as she did not remarry, at which time the business would go to her brother-in-law. Of course I made said brother-in-law, Lionel Neville, a greedy, unlikable creature.

Mix into the mortar a violent past, a few surprise wards, and voila—the Kate Clifford series had a firm foundation. And now for the murder and mayhem!

Candace Robb did her graduate work in medieval literature and history, and has continued to study the period while working first as an editor of scientific publications and now for some years as a freelance writer. She was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, grew up in Cincinnati, and has lived most of her adult life in Seattle, which she and her husband love for its combination of natural beauty and culture. Candace enjoys walking, hiking, and gardening, and practices yoga and vipassana meditation. She travels frequently to Great Britain.

Candace’s current passion is exploring fuller and more plausible interpretations of the lives of women in the 14th century than are generally presented. She also writes historical fiction as Emma Campion.

Learn more about Candace and her novels at her website, www.CandaceRobb.com, on her Facebook page, and on Twitter: @CandaceMRobb.

You’ll find all of her books available for purchase at your favorite bookstore or on-line retailer. And look for her newest novel, THE SERVICE OF THE DEAD, featuring Kate Clifford of York, out now in hardcover, e-book and audio book formats.

I have met residents of Shrewsbury who pronounce the city’s name like this: shrowsbry. I have met residents of Shrewsbury who pronounce the city’s name like this: shroosbry. I think this is a conspiracy to confuse and frustrate Yanks, and I cannot tell you which is the correct pronunciation. Both? The city’s Old English name isn’t much help: Scrobbesbyrig, which means “Fortified place of the scrubland region” from the Old English word scrobb, which is pronounced either shrob or – oh, never mind.

I have met residents of Shrewsbury who pronounce the city’s name like this: shrowsbry. I have met residents of Shrewsbury who pronounce the city’s name like this: shroosbry. I think this is a conspiracy to confuse and frustrate Yanks, and I cannot tell you which is the correct pronunciation. Both? The city’s Old English name isn’t much help: Scrobbesbyrig, which means “Fortified place of the scrubland region” from the Old English word scrobb, which is pronounced either shrob or – oh, never mind.