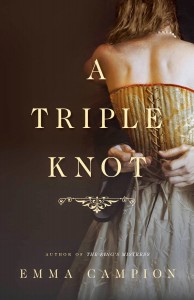

Today I am delighted to welcome my good friend, the critically acclaimed author Emma Campion, to discuss her newest book, A Triple Knot. This is a novel set in the 14th century, and it’s about Joan of Kent, renowned beauty and cousin to King Edward III. She is a young woman who is destined for a politically strategic marriage arranged by the king, except that Joan has other ideas. She secretly pledges herself to a knight, one who has become a trusted friend and protector. When the king—furious at Joan’s defiance—prepares to marry her off to another man, she must defend her vow. To complicate matters further, the heir to the throne—a man who would be known to history as Edward, the Black Prince—has his own plans for his beautiful cousin. The result is an enthralling story of political intrigue, personal tragedy, and illicit love.

Today I am delighted to welcome my good friend, the critically acclaimed author Emma Campion, to discuss her newest book, A Triple Knot. This is a novel set in the 14th century, and it’s about Joan of Kent, renowned beauty and cousin to King Edward III. She is a young woman who is destined for a politically strategic marriage arranged by the king, except that Joan has other ideas. She secretly pledges herself to a knight, one who has become a trusted friend and protector. When the king—furious at Joan’s defiance—prepares to marry her off to another man, she must defend her vow. To complicate matters further, the heir to the throne—a man who would be known to history as Edward, the Black Prince—has his own plans for his beautiful cousin. The result is an enthralling story of political intrigue, personal tragedy, and illicit love.

1. Emma, I’m intrigued by the epigraph at the beginning of your novel—a quote from Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead: There must have been a moment, at the beginning, where we could have said—no. But somehow we missed it.

Would you explain the thinking behind that choice, and how it sets the theme for your book?

This comes at the very end of the play when Guildenstern’s fate is clearly sealed, and I end A Triple Knot with Joan coming face to face with her fears about Ned’s (Prince Edward’s) true character. She might voice the same lines, but in first person singular. And just as it’s not at all clear that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern ever truly could have refused a summons by the King and Queen of Denmark, I intend the reader to doubt that Ned would have accepted a definitive no from Joan. Deep down she’s known that all along, but refused to see it.

2. Your earlier novel The King’s Mistress about Alice Perrers was written in the first person. For this novel, though, you’ve used the third person shifting viewpoint, and we see into the minds of several of the characters. Why did you choose this structure for the book?

Alice was an outsider at court, so it felt right to tell her story from her point of view. And my editor at Century felt first person would inspire my readers’ empathy, combating her difficult reputation.

I wanted to tell Joan’s story from multiple viewpoints to convey a sense of the wheels within wheels turning around her, influencing her choices and her fate. And, to be honest, I felt horribly limited in first person; I’ve always written from several points of view except in one short story. I enjoy shifting perspectives.

3. You have written a dark edginess into the relationship between Edward the Black Prince and his cousin Joan. Did you base this on evidence that you discovered about Ned through your research, or was it a purely creative decision?

Prince Edward was ruthless in war; his raids across Gascony in the mid 1350s  were so destructive that one wonders what he thought would be left for his father to rule. And though we now have a letter proving that Froissart’s account of a massacre of the people of Limoges was an exaggeration, his troops did wreak significant damage to the town, including the cathedral. Reading between the lines, I’ve always felt he modeled himself after his great grandfather, Edward I, who took pride in being “the Hammer of the Scots” and also spent a fortune fortifying Wales against the Welsh after he’d done his best to break them. Prince Edward’s style of rule in the Aquitaine is wildly inconsistent, with bursts of violent suppression. He turned a deaf ear to his most experienced counselors. I mixed this with how long he’d delayed marriage (quite late for an heir to the throne), the suddenness of his wooing Joan (within a few months of Thomas’s death), and Joan’s choice to be buried not beside him but beside Thomas, and came up with the character of Ned in my book. I love his complexity, I love the edginess.

were so destructive that one wonders what he thought would be left for his father to rule. And though we now have a letter proving that Froissart’s account of a massacre of the people of Limoges was an exaggeration, his troops did wreak significant damage to the town, including the cathedral. Reading between the lines, I’ve always felt he modeled himself after his great grandfather, Edward I, who took pride in being “the Hammer of the Scots” and also spent a fortune fortifying Wales against the Welsh after he’d done his best to break them. Prince Edward’s style of rule in the Aquitaine is wildly inconsistent, with bursts of violent suppression. He turned a deaf ear to his most experienced counselors. I mixed this with how long he’d delayed marriage (quite late for an heir to the throne), the suddenness of his wooing Joan (within a few months of Thomas’s death), and Joan’s choice to be buried not beside him but beside Thomas, and came up with the character of Ned in my book. I love his complexity, I love the edginess.

Joan of Kent. Photo credit: gwu.edu

4. How long did it take to write this novel, and did you face any significant challenges in putting Joan’s story together?

Three years, which is a long, long time for me, considering I write my series books in 9 months to a year. At first it was Joan who eluded me, which was a surprise, as she’s a strong secondary character in both A Vigil of Spies (Owen Archer #10) and The King’s Mistress. But in both books she’s a mature woman, and her singular act of disobedience is well behind her.Now, in telling the story of her knotty marital situation, I needed to understand her motive in disobeying King Edward when she knew full well the danger—her father had been executed for displeasing Edward’s mother. The fierce Plantagenet temper was a point of pride. What could drive a twelve-year-old to take such a risk? Joan must have known she was being raised in the royal household for the very purpose of making a marriage that would benefit her cousin the king. So what drove her to disobey him and choose her own husband? Historians for whom I have great respect shrug off the story of her clandestine marriage as a lie that she and Thomas made up so she might escape an unhappy marriage. But the papal court believed their story, and I just did not find it plausible that the pope would be duped by such an obvious ploy. So it fell to me to find her motive. Once I found the proposed betrothal I felt confident I had a story.

And then…I learned about seven months before the book was due that my publisher wanted the book considerably shorter than my editor had originally indicated. She thought she’d told me…. So after a week of panic, I proposed ending Joan’s story just after her marriage to Edward, Prince of Wales and the Aquitaine. My editor loved the idea. The crisis was averted, but it meant starting over, because now the pacing was all wrong.

5. One of the difficult things about writing a novel centered on a historical figure is the decision an author must make about where the story should begin and where it should end. A Triple Knot covers only part of the fascinating life of Joan of Kent, albeit a very gripping part. Did you know exactly where the book would end when you began writing?

Hah! See my answer to the previous question! Once I’d found the betrothal I had a date at which I felt Joan and Thomas’s story began. I was tempted to end the story with Thomas’s death. But I felt I needed to play out Prince Edward’s obsession. So I tried out the ending with my editor and she loved it.

6. I suspect that most writers can point to a favorite scene in each of their books – either a scene that was a pleasure to write, or one that was so challenging that the finished product, after a great deal of effort, was enormously satisfying. Do you feel that way about any particular scene in A Triple Knot?

What comes to mind is the scene at the Round Table tournament where Joan witnesses her father-in-law Earl William collapse, and she watches as his wife Catherine lies down on the pallet beside him, trying to coax him awake. When King Edward enters the pavilion, Catherine rushes to stand in respect, her garter slips down, and Edward retrieves it. This is a variation on the rumor spread by the French that the symbol of King Edward’s “noble” order of the garter had been inspired by something so silly (and scandalous) as the Countess of Salisbury’s garter, which fell down while she and the king were dancing. After lengthy debates about “whose garter?” my friend Laura Hodges encouraged me to come up with my own story. And so I did.

7. Can you tell us a little about the title, A Triple Knot? Was there an earlier working title?

Third title’s the charm in this case. First came The Hero’s Wife, when I envisioned a much longer book in which Joan’s earlier marriage(s) served as a long prelude to her becoming the wife of Edward of Woodstock, the hero of Crécy and Poitiers. When the latter marriage was relegated to a possible follow-on book, I chose Rebel Pawn as a working title. I had some fun with that, creating chapter headings relating the action to a chess game. But I never warmed to the title. One day, as I was organizing my notes for the third (and final!) draft, I realized I was describing a triple knot—Thomas, Will, Ned. And there it was.

8. I know that you have been to Britain several times for research. Was there a site that you visited that helped you envision a particular setting?

Although Windsor Castle has undergone significant renovations since the 14th century, the bones of the earlier castle are clear enough that scenes set within it are a gift, easily envisioned. For most of the royal palaces and noble residences I cobble together written descriptions with old drawings/paintings as well as bits and pieces from my frequent treks through medieval sites in England, Scotland and Wales. But Windsor is still a royal residence, so alive.

Emma Campion did her graduate work in medieval literature and history, and has continued to study the period while working first as an editor of scientific publications and now for some years as a freelance writer. She was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, grew up in Cincinnati, and has lived most of her adult life in Seattle, which she and her husband love for its combination of natural beauty and culture. Emma enjoys walking, hiking, and gardening, and practices yoga and vipassana meditation. She travels frequently to Great Britain.

Emma Campion did her graduate work in medieval literature and history, and has continued to study the period while working first as an editor of scientific publications and now for some years as a freelance writer. She was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, grew up in Cincinnati, and has lived most of her adult life in Seattle, which she and her husband love for its combination of natural beauty and culture. Emma enjoys walking, hiking, and gardening, and practices yoga and vipassana meditation. She travels frequently to Great Britain.

Emma’s current passion is exploring fuller and more plausible interpretations of the lives of women in the 14th century than are generally presented.

Learn more about Emma and her novels at her website, www.EmmaCampion.com, on her Facebook page, and on Twitter: @CandaceMRobb.

You’ll find A Triple Knot available for purchase at your favorite bookstore or on-line retailer.

From my bedroom I could see St. Deiniol’s churchyard, and I soon learned that there had been churches on this site dedicated to the 6th century Welsh saint for over a thousand years. Some elements of the current edifice have been traced back to the 14th century, but St. Deiniol’s had been through several restorations and one fire, and as a result, most of it was now 19th century work. Still, once I was inside, it felt awfully old to me.

From my bedroom I could see St. Deiniol’s churchyard, and I soon learned that there had been churches on this site dedicated to the 6th century Welsh saint for over a thousand years. Some elements of the current edifice have been traced back to the 14th century, but St. Deiniol’s had been through several restorations and one fire, and as a result, most of it was now 19th century work. Still, once I was inside, it felt awfully old to me.

The past, of course, was my reason for being in Wales at all. And so I spent most days studying Anglo-Saxon history in the library while occasionally making my way to the little church that had its history in its walls and, thanks to Edward Burne-Jones, in windows that so beautifully evoked the medieval.

The past, of course, was my reason for being in Wales at all. And so I spent most days studying Anglo-Saxon history in the library while occasionally making my way to the little church that had its history in its walls and, thanks to Edward Burne-Jones, in windows that so beautifully evoked the medieval.