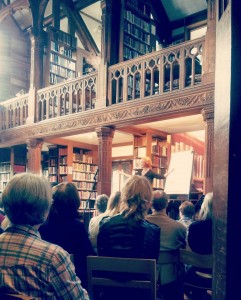

A few months ago the e-newsletter Shelf Awareness ran a photo gallery of remarkable libraries. One picture that particularly caught my attention was of Gladstone’s Library in Wales. Here’s the photo:

Intrigued and a little bit enchanted, I immediately went to the Library’s website to learn more about it. I discovered that its collection had been founded by Prime Minister William Gladstone at the end  of the 19th century, and that the building in which it is housed opened in 1902 as the National Memorial to Mr. Gladstone. It now contains over 200,000 books, and it is open to the public.

of the 19th century, and that the building in which it is housed opened in 1902 as the National Memorial to Mr. Gladstone. It now contains over 200,000 books, and it is open to the public.

Gladstone’s Library is wonderfully supportive of writers. It hosts book launches, writing workshops, poetry and short story contests, and an annual literary festival. It is also a residential library, so a researcher or a writer can stay there and work. I’d never heard of such a thing! Reviews on TripAdvisor describe it as a peaceful retreat set in beautiful grounds, and looking at the photos, I can believe it.

In addition to all of this, a few years ago Gladstone’s Library instituted an annual Writer-in-Residence program. The writers chosen to participate in the program receive board and lodging, access to the library, and time to write and to think.

In return, the writers each offer a day-long creative writing workshop or an “Evening With” event. And, I read, applications were being accepted for the 2014 Writer-in-Residence scheme.

Writer-in-Residence. The words were not typed in bold face, but that’s how I saw them; and as soon as I saw them I began to dream. What would it be like to stay in Wales for a time, to work on a manuscript, to conduct research, to teach a workshop and to retreat from the world and immerse one’s self in the writing process? How wonderful a gift that would be! Only, what were the chances of someone like me, a debut author, being considered for such a thing? And were Americans even eligible?

I quickly e-mailed the Library. Upon receiving their assurance that Americans could apply, I carefully prepared the information requested for consideration: a copy of my book, a CV, a description of what I would be working on at the library, and a brief essay on liberal values. That last item took the most time, and a great deal of thought. Mr. Gladstone would have approved. (And I owe a debt of gratitude to my editor at HarperCollins UK for negotiating the British Postal Service for me.)

Then I waited. It would only be six weeks or so (which seemed like an eternity) until the writers for 2014 would be determined. But I was busy – hard at work revising my current work-in-progress (still working on that); consulting with my agent on the sale of my second book about Emma of Normandy; planning and setting out on a working holiday to Britain. Always, though, niggling at the back of my mind, was the slender thread of hope that I might, just might, one day go to Gladstone’s Library.

Does this tale have a happy ending? Well, as I have discovered repeatedly over the last two years, miracles do happen. I am proud to announce that for two weeks in the autumn of 2014 I will be the Writer-in-Residence at Gladstone’s Library in Hawarden, Flintshire, Wales. It is an honor and a challenge, and I am enormously grateful to the Library and to the committee of judges for granting me such a wonderful opportunity.

And now, yes, I’m getting back to revising that work-in-progress.