Many of Britain’s historical sites are clearly visible and extremely well preserved, sometimes as museums or parks. London’s Tower, for example, accommodates thousands of visitors a day. The ruins of the abbey at Bury St. Edmunds or the castle at Guildford have become the stunning centerpieces of city parks.

Abbey remains, Bury St. Edmunds

Guildford Castle. Norman.

But there are other less well known monuments that dot the English landscape: stone circles like the Rollrights in the Cotswolds, monoliths like the Rudstone in Yorkshire, and over a thousand iron age hill forts. Many of them are marked on Ordinance Survey Maps and can be found without too many wrong turns. There are some, though, that are only of interest to history geeks and curious authors, and these take a little more effort to find.

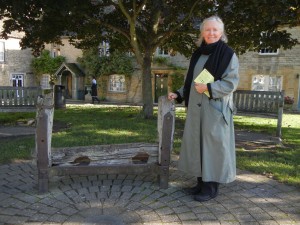

On our recent visit to England my husband and I went in search of two such places, both dating from the early 11thcentury reign of King Aethelred II. Our first destination was Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. In A.D. 1013 the Danish king, Swein Forkbeard, invaded Britain, and set up camp near Gainsborough, landing his fleet of Viking war ships along the banks of the River Trent. I had read that the earthworks of that Viking camp were still visible at a place now known as Castle Hills, and I wanted to see if I could locate them.

So, on a beautiful fall day we set out from Stow-on-the-Wold via the Fosse Way – one of the four Roman roads built to facilitate the movement of the legions around England. Somewhere northeast of Warwick we crossed another Roman Road, Watling Street, and so we entered the ancient Danelaw. In the Viking Age this area had been settled by wave after wave of Scandinavian invaders, and in the 11th century certain nobles with lands hereabouts were somewhat ambivalent about their allegiance to the English king. When Swein arrived with a huge army at his back they quickly transferred their allegiance to him.

River Trent – imagine it filled with Viking longships

We arrived at Gainsborough just after mid-day and stopped first at the Old Hall, which is situated on the site where Swein and his son, Cnut, had their headquarters. The 15thcentury Old Hall would have been worth a visit in its own right – one of the best preserved manor houses in England. Richard II and Henry VIII were entertained there, and on the day we visited it was swarming with school children who were getting a wonderful dose of high medieval history.

Gainsborough Old Hall

I, however, was concerned with events a little further in the past, and so we stayed only long enough to inquire about the site of the Danish camp. The directions we were given were vague, taking us out of town and up a hill away from the river. There was forest on both sides of the road where the camp should have been and little to be seen from the street, so we left the car and followed a path into the woods. It led to a derelict football field, and stepping over a low berm between the forest and the playing field, I theorized aloud that this might be one of the earthworks of the Danish camp. My engineer husband explained that it was probably a leftover from the grading for the field, not a remnant from a one thousand year old fort.

The berm between the playing field and forest.

Disappointed but undeterred, I accosted a pensioner who was walking his dog along the edge of the woods and asked if he knew where the Danish camp was. He waved his arm to take in the entire hilltop.

“They were all over this place. It was the highest point around, and at that time the River Trent ran nearer the foot of this hill. Yes, there are ridges – over there,” he said, pointing. “Some say they are the remains of a fort, but I don’t know.”

Of course they would have sited their camp on high ground, I thought, just like the men who built the Iron Age hill forts a thousand years before them, and like William the Conqueror who came fifty years after them. These men knew that a fort on a hill was most easily defended.

We thanked our guide and continued our search in the area he’d pointed out. For some time the signs of fortification continued to elude us, and I longed for a rune stone saying “Swein slept here,” but no such luck. Eventually, though, we found what we’d been looking for: ridges that I imagined marked ditches and boundaries, covered now with long grass, brush and trees, and many feet higher than the low berm at the edge of the field.

The engineer, standing on Swein’s fortifications

There was no marker to confirm the theory. The Danes had left long ago, and even the inhabitants of Gainsborough were vague now about what once stood here. Their 15thcentury Old Hall was, of course, of vastly more archaeological significance than the temporary camp of a Danish king. Nevertheless, a thousand years after the Danes built it, the remains of their fortification were beneath our feet. Their ships were gone, and whatever buildings they may have raised crumbled long ago, but the land, it seemed to me, left untouched for a millennium, still remembered them.

Looking down from atop the earthworks

My favorite part of Christmas is the singing of carols – in the midst of darkness a plea for light. The music of the carols, some of their melodies floating down to us from the Middle Ages, can lift hearts even in times of deepest darkness.

My favorite part of Christmas is the singing of carols – in the midst of darkness a plea for light. The music of the carols, some of their melodies floating down to us from the Middle Ages, can lift hearts even in times of deepest darkness.