I wrote a post in April about English Great Halls, and this week I’ve decided to consider the larger question of English royal palaces in the early medieval period, prior to 1066. It is much more difficult than you might think.

When you see or hear the word “palace” probably something like this immediately pops into your mind.

But this little charmer was built by Ludwig of Bavaria in the 19th century, so forget it. We’re not going there today. We’re considering English royal palaces of the 11th century. Not castles, mind you, which were built for defense, but palaces that were intended specifically as royal residences. They looked more like….well, you know, we really don’t know what they looked like. All we can do is guess.

One of the foremost archeologists in Britain, Martin Biddle, has this to say about the subject:

“In what kind of palace did King Edgar live, who ‘showed by his impressive coronation ceremony at Bath in 973 that he grasped the political value of external magnificence?’ What were the halls and chambers of wood or stone which Asser attributed to Alfred? If the great series of royal churches in Winchester is anything to judge by, the old English royal palace which completed that complex will have been of Carolingian scale and magnificence, and everything in the art and architectural history of Alfred’s time suggests the possibility that actual continental models, Aachen itself perhaps, may have influenced it. But we know nothing concrete.”1

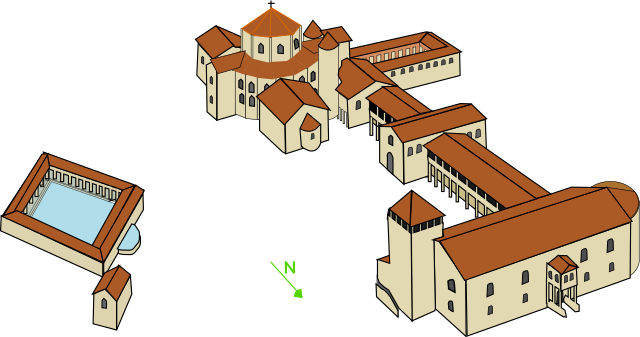

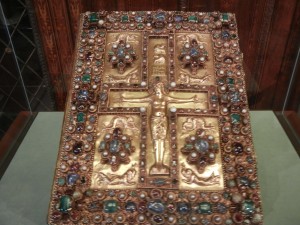

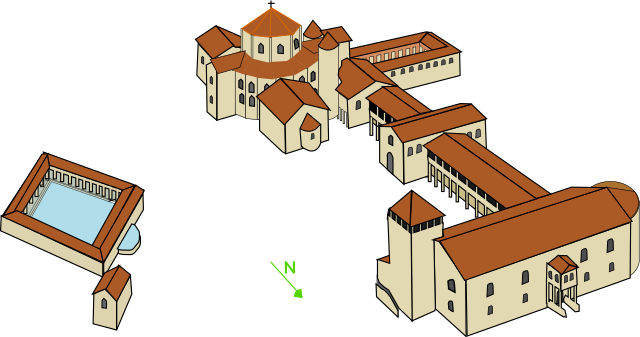

The palace at Winchester has been described as splendid, made of stone with glazed windows, an elaborate residence. The Anglo Saxons loved display and decoration, so the hall would have featured carved decoration on wood, inside and out. And Professor Biddle has given us a hint that it may have looked something like Charlemagne’s palace at Aachen. Well, there’s nothing left of Charlemagne’s palace now except for the royal chapel. But archaeologists think it may have looked something like this:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Ah. Speculation upon hypothesis. Well, let’s run with it because what other choice do we have?

What we see in the Aachen drawing is not one building, but a complex of buildings, connected by covered walkways. This makes a great deal of sense to me, and I especially like the idea of those covered walkways, given the British climate.

John Burke, in his book “Life in the Castle in Medieval England” observes that from Alfred’s time on, the central building of the royal palace would have been the Great Hall where business was conducted and communal feasts held. The hall may have had chambers recessed into its walls and partitioned off for privacy. If the hall had two stories, there would have been a gallery on the second floor where the king could stand above it all and keep a gimlet eye on the activities below. We know, for instance, that such a gallery existed in the Old Minster at Winchester where the king attended Mass in a second story royal box.2

The Great Hall was merely the central building, though. In the Old English poem Beowulf King Hrothgar retires from the great hall to go to his bed. Beowulf himself, a visitor to the palace, was lodged somewhere outside the hall. One imagines separate quarters where guests could sleep, connected to the hall, perhaps, by those covered pathways. And speaking of bedchambers, the royals would have used them for more than just sleeping. The chamber would have been far more complex than today’s bedrooms and more highly populated. The queen’s bedchamber, for example, would have been a place of refuge for the women if things got too rowdy in the hall.3 It’s my belief that the queen might very likely have had her own building in the complex divided into rooms earmarked for different purposes.

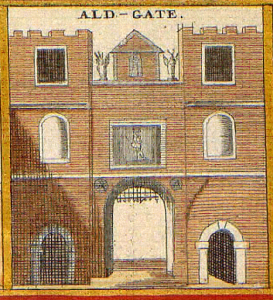

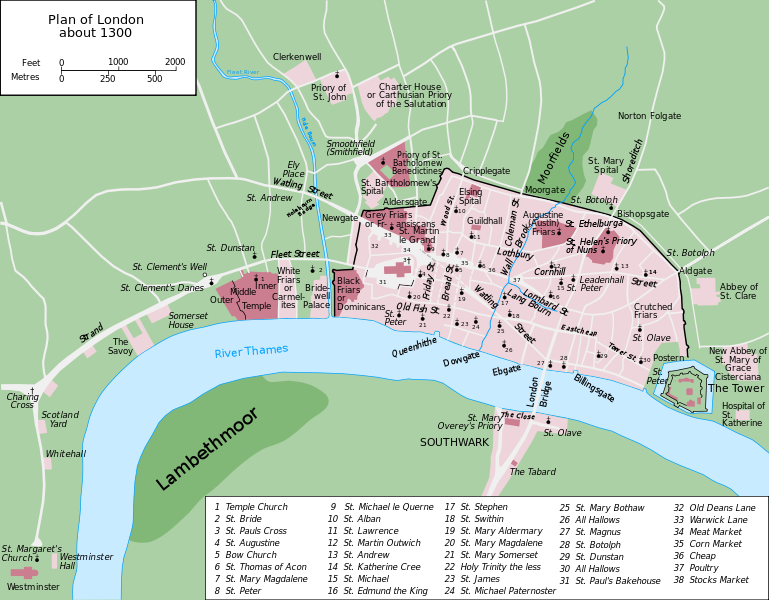

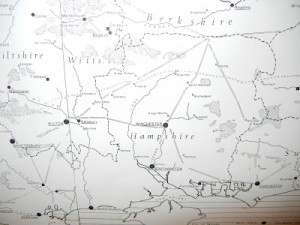

There would have been other buildings in the magnificent, urban palace complexes of London, Canterbury and Winchester: kitchens, stables, and a chapel, certainly; possibly weaving sheds, a forge, and an armory as well. At Winchester there was a mill. The rural palaces, like those at Headington, Cookham and Calne, would have had all these things and would have been the focal points of large estates that included entire villages. There were hunting lodges too, where the king and his retinue could enjoy a little recreation and where, apparently, regulations regarding arms were somewhat relaxed. King Edmund the Elder was killed in an altercation with a robber at his hunting lodge at Pucklechurch in 946.

One vexing question that remains is whether the palaces were made of wood or of stone. We can’t say for certain, but it’s likely that both stone and timber were utilized. The hunting lodge at Corfe appears to have been made of stone, and if stone was used for a hunting lodge, surely it would have been appropriate for the more magnificent, urban palaces.

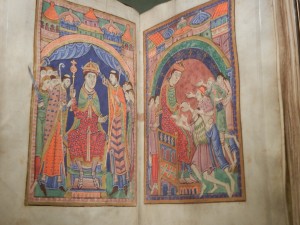

Today, though, nothing remains of the palaces of the early English kings – not even ruins. Granted, there is an image of Edward the Confessor’s palace in the Bayeux Tapestry, but that is probably drawn, not from a familiarity with the actual building, but from “a repertoire of architecture elements typical of contemporary manuscript art.”4

So now these courts are empty,

and the rich vaults of the vermillion roofs

shed their tiles. The ruins toppled to the ground,

broken into rubble, where once many a man

glad-minded, gold-bright, bedecked in splendor,

proud, full of wine, shone in his war-gear,

gazed on treasure, on silver, on sparkling gems,

on wealth, on possessions, on the precious stone,

on this bright capital of a broad kingdom.

From the Old English poem, The Ruin, 8th Century

1 Welch, Martin, Discovering Anglo-Saxon England, Pennsylvania University Press, 1993.

2 Burke, John, Life in the Castle in Medieval England, Barnes Noble, 1992.

3 Webb, Diana, Privacy and Solitude: The Medieval Discovery of Personal Space, Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

4 Lewis, Michael J., The Real World of the Bayeux Tapestry, The History Press, 2008.

Or compare Lindsey Davis’s 1997 “The Course of Honour” with her soon to be released title “Master and God”. Much less going on in the more recent covers, don’t you think?

Or compare Lindsey Davis’s 1997 “The Course of Honour” with her soon to be released title “Master and God”. Much less going on in the more recent covers, don’t you think?