Heorot

The warriors hastened, marched together until they might see the timbered hall, stately and shining with gold; for earth-dwellers under the skies that was the most famous of buildings in which the mighty one waited – its light gleamed over many lands.

Beowulf, 8th, 9th, 10th, or 11th century depending on which scholar you prefer

The Hall of the Green Knight

And behind it there hoved a great hall and fair:

Turrets rising in tiers, with tines at their tops,

Spires set beside them, splendidly long,

With finials well-fashioned, as filigree fine.

Then attendants set tables on trestles about,

And laid them with linen; light shone forth,

Wakened along the walls in waxen torches.

The service was set and the supper brought;

Royal were the revels that rose then in hall

At that feast by the fire…

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, 14th century

Meduseld

“… there stands aloft a great hall of Men. And it seems to my eyes that it is thatched with gold. The light of it shines far over the land. Golden, too, are the posts of its doors.”

…Inside…the hall was long and wide and filled with shadows and half lights; mighty pillars upheld its lofty roof…the floor was paved with stones of many hues; branching runes and strange devices intertwined beneath their feet. They saw now that the pillars were richly carved, gleaming dully with gold and half-seen colours. Many woven cloths were hung upon the walls, and over their wide spaces marched figures of ancient legend, some dim with years, some darkling in the shade.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, 1954

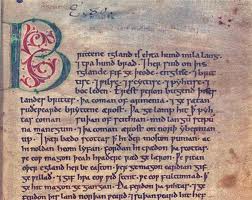

Descriptions of the Great Hall have come down to us in legend and story for over a thousand years. Norse longhalls, Anglo-Saxon mead halls, medieval castle halls — the buildings existed in the real world, but how closely did the glorious descriptions fit the reality?

For several years now I have been trying to answer numerous questions about what the great hall of an 11thcentury English king might have looked like.

How many royal halls were there in Aethelred’s time?

Probably quite a few: at Winchester, London, Oxford, Canterbury, Cheddar, Colne, Cookham, and likely other places as well – all royal properties where King Aethelred II held councils over the course of his thirty-eight year reign.

Were they built of stone or wood?

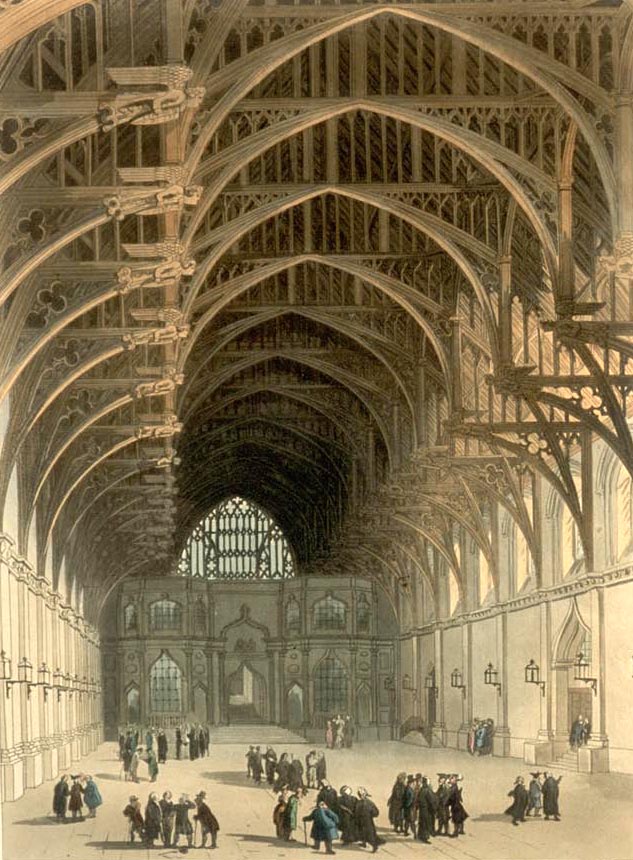

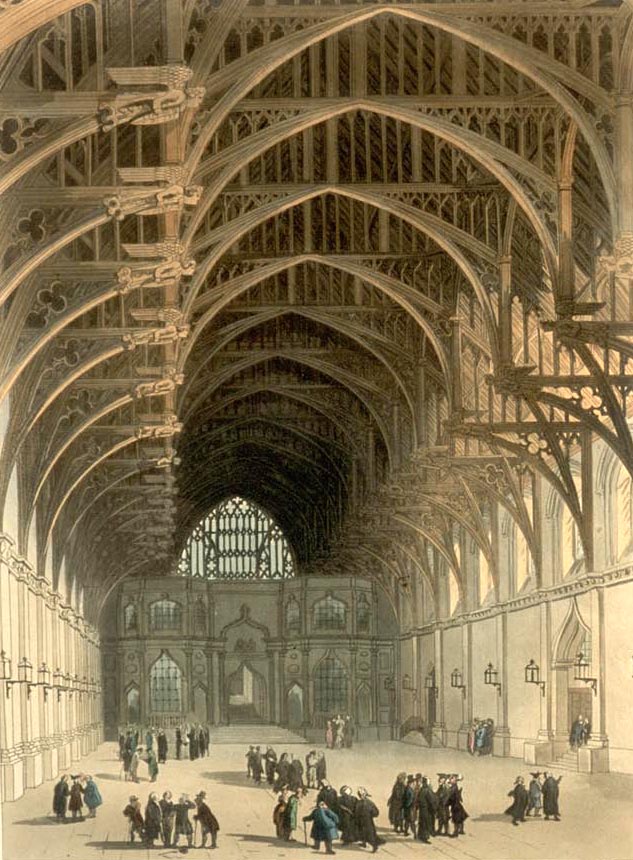

No one can say for certain. After 1066 the Normans were determined to put their mark on Britain, and what better way to do it than to destroy all the royal buildings and re-make them in their own fashion? The Anglo-Saxons built stone churches, and I believe that they must have built at least some of their royal great halls in stone. The ceilings would have been made of vaulted timbers, and the roof material would have been slate or, in some cases, of thatch. Aethelred’s son, Edward, built his great hall at Westminster in stone, but in 1097 William Rufus, son of William the Conqueror, tore it down and built a new one. That hall is still standing, and is the oldest Parliament building.

Westminster Hall, as drawn by Thomas Rowlandson & Augustus Pugin for Ackermann’s ”Microcosm of London” (1808-11). Wikimedia Commons

Did they have one story or two?

Even the larger halls may have had a partial second story – a more private chamber for the royals. The 13th century Great Hall at Winchester has one. Some smaller halls were built over a vaulted basement so that the hall was accessed by an external stairway.

Boothby Pagnell Manor, Lincolnshire, from about 1200. Wikimedia Commons

Were there windows?

There would have been windows, although probably not large ones, and probably high up.

Did the windows have panes?

We know that Alfred the Great had glass window panes in his hall, built one hundred years before Aethelred was born. Other possible materials for window panes were thin slices of horn, as well as linen and leather. The window openings, whether paned or not, would have had wooden shutters.

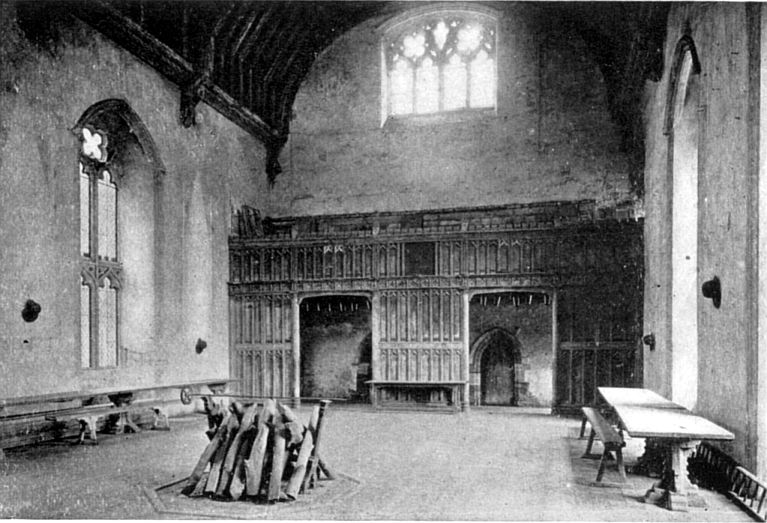

How was the hall heated?

A central fire pit, used for roasting meats in the earliest halls, was certainly a fixture for centuries.

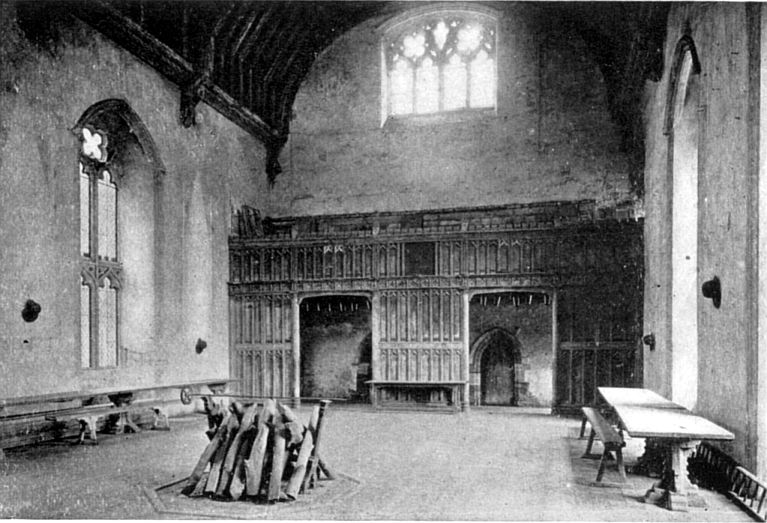

Penshurst Place 13th Century. Note screens passage. Wikimedia Commons

Where were the doors?

There were two possible designs for doorways. The hall was rectangular, and sometimes there were two main entrances at the foot of the hall, one on each of the long walls. Alternatively, there could have been large, central doors on the short wall at the bottom of the hall. Either way, just inside the doors a sort of vestibule would have been created, certainly in Aethelred’s time, by the use of movable screens. This was called the screens passage. The screens would prevent sudden gusts of wind from blowing smoke from the central fire in all directions when the hall doors were opened. In later halls the screen was fixed and part of the building itself.

Over the course of the Middle Ages, the major elements of the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall would be incorporated into castles, great houses and even universities throughout Britain.

19th century dining Hall, Downing College, Cambridge University

A perfect example is the dining hall of Hogwarts, filmed at Christ Church College, Oxford. (The dining hall at Downing College, Cambridge, is not so lavish, but it’s where I dined during my sojourn there, and where I was accorded the honor of a seat at the high table one night.)

So in spite of the Norman’s best efforts, the memory of the Anglo-Saxon Great Hall still survives in real life as well as in films and in literature.

Winchester Great Hall

While the king was at Bath teams of workers had descended upon Winchester’s great hall, and by Easter day the massive chamber was resplendent — newly thatched and freshly painted. The carved acanthus leaves that twined sinuously around the enormous oaken columns and roof beams had been regilded so that they gleamed golden in the torchlight. Silken streamers looped overhead from pillar to pillar in clouds of gold and white. The tables had been laid for the great Easter feast, covered with linens and garlanded with flowers, and upon the royal dais the high table wore a cloth of shimmering gold.

Patricia Bracewell, SHADOW ON THE CROWN, Viking, 2013

… compare Diana Gabaldon’s first book with the most recent offering in the Outlander Series.

… compare Diana Gabaldon’s first book with the most recent offering in the Outlander Series.

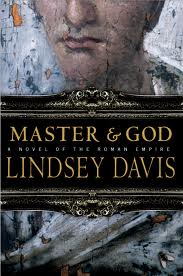

Or compare Lindsey Davis’s 1997 “The Course of Honour” with her soon to be released title “Master and God”. Much less going on in the more recent covers, don’t you think?

Or compare Lindsey Davis’s 1997 “The Course of Honour” with her soon to be released title “Master and God”. Much less going on in the more recent covers, don’t you think?