The episode begins in Norway as Freydis arrives at the healer’s cabin, alarmed and in search of her friend Yrsa. Unfortunately, she finds her. She also finds the Christian zealot who we learn is named Jarl Kåre. Later we will learn that as a boy he witnessed his brother being sacrificed at Uppsala, which is what’s made Kåre a Christian zealot. By the end of the episode, after he has consulted the spámaðr, it looks like Jarl Kåre and his minions will destroy the temple at Uppsala and perhaps take their vengeance to Kattegat.

In the sagas, Freydis is a female warrior and daughter of Erik the Red, and yes, that is how she is portrayed in this series. But her plot line, as far as I can tell, while fascinating, is unrelated to the Icelandic sagas in which she appears. If someone knows otherwise, please alert me.

Back to London where we are tantalized by the hint that Olaf, as he prepares to depart England and return to Norway, is planning something that might provoke Cnut to try to destroy him. As yet we don’t know what Olaf is planning.

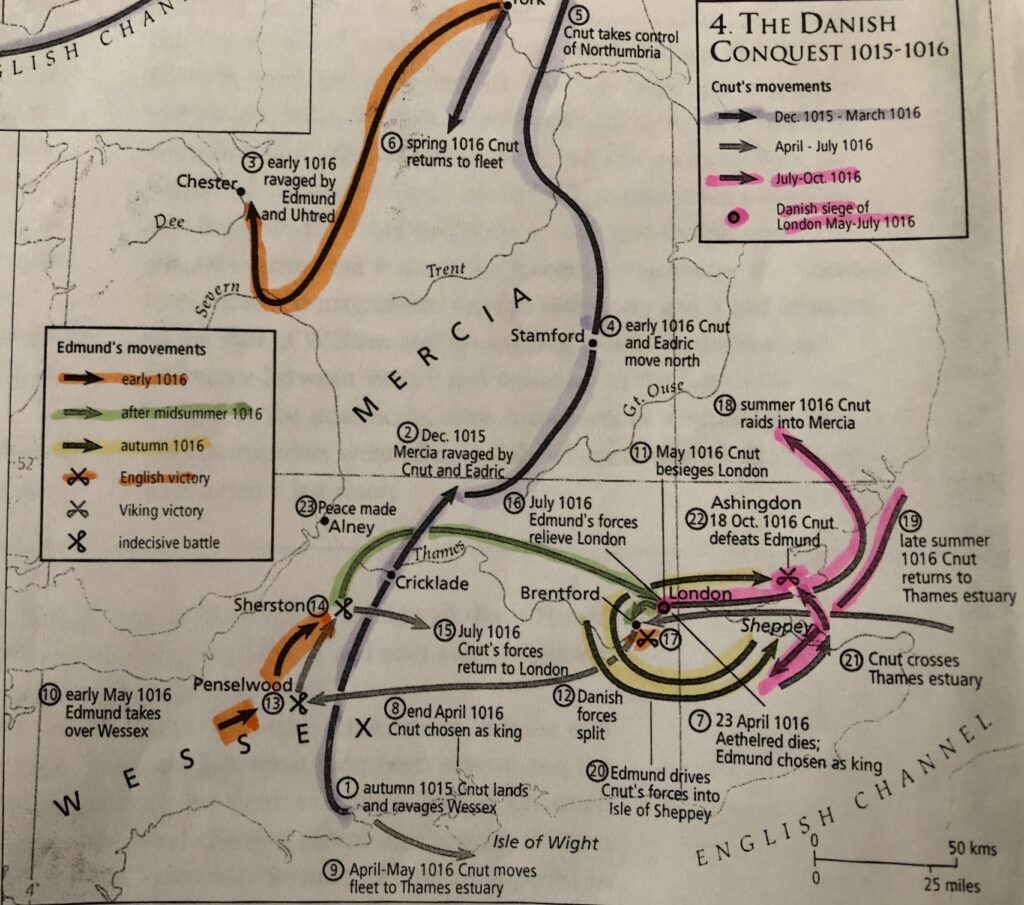

Harald, too, is leaving England. He asks Cnut, who is remaining in England to rule as king, if he’s sure he knows what he’s doing. So, let’s look at the history. Although Cnut’s invasion of England is presented in this series as retaliation for the 1002 St. Brice’s Day Massacre, it is now 1016/17. Cnut’s father Swein Forkbeard died in 1014 which made Cnut’s elder brother, Harald (Yes!!! Another Harald) King of Denmark. Although Swein Forkbeard died 2 months after he conquered England, Cnut nevertheless claimed his right as Swein’s heir to the English throne. Unfortunately for Cnut, Æthelred and his viking allies (Olaf and Thorkell) drove Cnut from England back to Denmark in 1014, but Cnut returned in 1015 to try to capture what he considered his rightful claim to England. He had no other choice, really. His brother was already king in Denmark, so Cnut had to grab a kingdom for himself, and he chose England. So yes, he knew what he was doing.

Now, about those nobles who bent the knee to Cnut, persuaded by the sight of Earl Leofric of Northumbria hanging from a noose, presumably chosen by Godwin as the sacrificial lamb. That’s really interesting because, yes, there were a number of English nobles executed by Cnut in 1017. Leofric wasn’t one of them, although a relative of his was. A gentleman named Northman. Leofric’s father and then Leofric himself (who was not hung by Cnut) eventually were installed as earls of Northumbria by Cnut, so the thinking is that Northman might have been involved, along with Eadric and several other nobles, in fomenting a rebellion against Cnut. Leofric and Godwin, by the way, were enemies through Cnut’s reign and beyond.

But why is Edmund Ironside still alive? He died on Nov. 30, 1016, probably from wounds that he received at Assandun on October 16. He died about a full year before Eadric Streona was executed. This series is going to have to dispose of him somehow. I’m curious to see how it will happen.

And now we see Cnut and Emma bonding over his need for England’s wealth in order to build his great northern empire. Yes, Cnut was ambitious, and it’s quite likely that Emma was an advisor. Cnut did, apparently, try to balance his need to reward his Danish followers with his need to reconcile himself to the English nobility. Emma would have been instrumental in assisting him with that because she had personal connections to the English elite. She probably spoke Danish because her mother was Danish so she could communicate easily with Cnut. She saw herself as a peaceweaver between Cnut and the English people. What’s really missing here are the ecclesiastics. The archbishops of Canterbury and especially Wulfstan of York would have been close advisors to Cnut at this time. But, you know, you just can’t include everybody when you’re trying to write a historical drama. An archbishop in all his ecclesiastical finery cannot hold a candle to the sight of Emma in bed with Cnut. I get it.

Harald and his fleet arrive in Kattegat, and when he meets with Jarl Haakon he asks for her help against his elder half-brother, Olaf. They both want to be king of Norway, and this will be a problem. This is true. My Norse history is spotty, but I know that Cnut, Olaf, and Harald were all rivals for the Norse throne over several decades.

The next scene takes us into Fantasyland because Olaf arrives in Jelling and meets with Cnut’s wife Ælfgifu, queen of Denmark, who is flanked by her 2 sons. Did Cnut have a wife named Ælfgifu? Yes. Was she a Mercian? Yes. Did they have 2 sons? Yes. Was she queen of Denmark? Never.

While Ælfgifu of Northampton may have been in Denmark at this time, the king of Denmark was—as I mentioned earlier– Cnut’s older brother, Harald. This imaginary meeting between Olaf and Ælfgifu, where he has the thankless task of reporting what Cnut is up to with Emma in England, sets up both a coming conflict between Olaf and Cnut, but also a coming conflict between Ælfgifu and Emma. And that certainly existed. I’ll tell you more about Ælfgifu after I’ve seen the next episode.

Episode 6 ends with Cnut receiving a long and apparently alarming missive from Denmark. He tells his huscarle to summon a priest and prepare his ship for departure. Then he turns to Emma who’s waiting for him in bed and he says slowly, “I must ask you a question. Please. Answer carefully.”

And THAT is an excellent cliff-hanger.