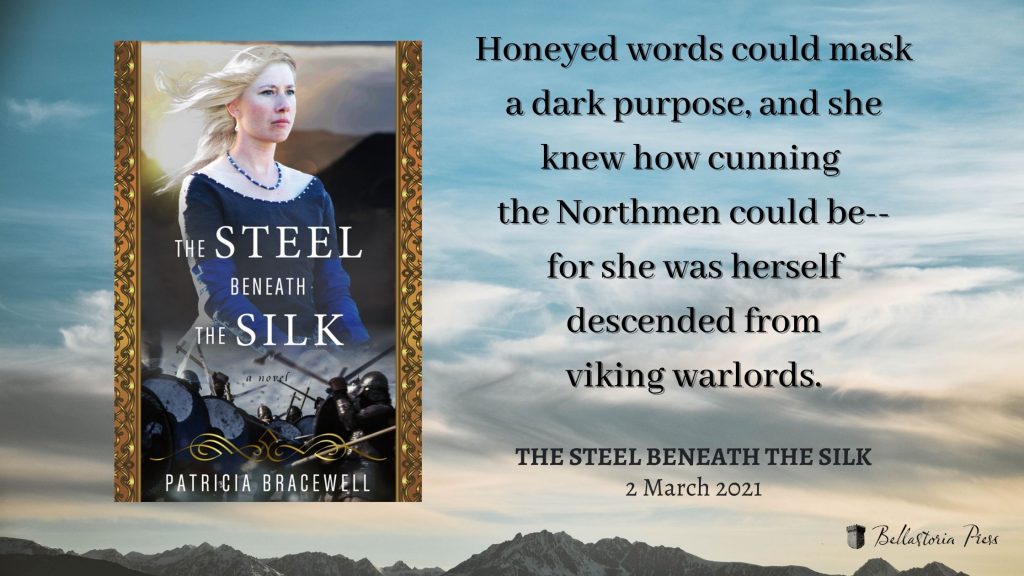

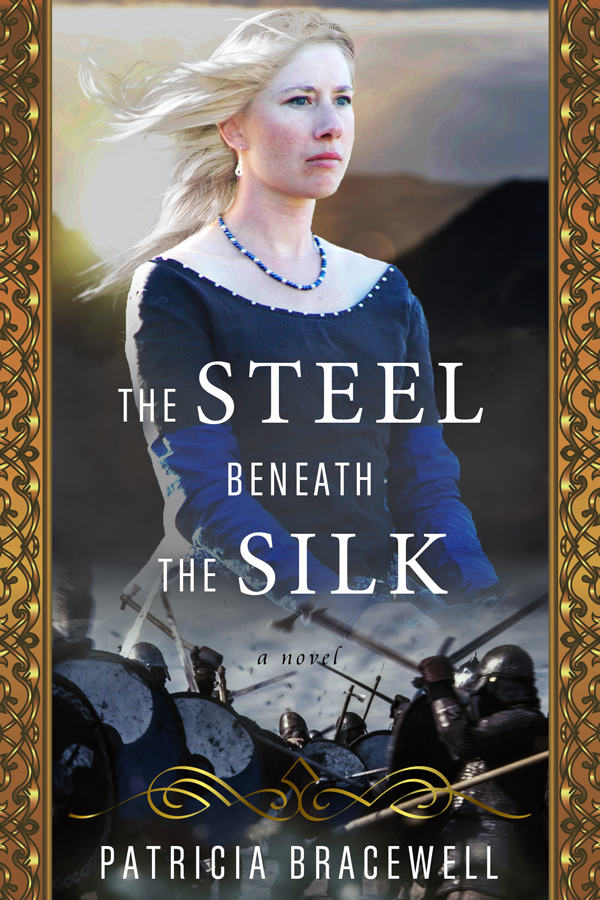

In The Steel Beneath the Silk, the novel that concludes my Emma of Normandy Trilogy, several characters appear who are new to the story. One of them is Cnut’s mum. Who was she? Of course, her son Cnut is well known as a Danish warrior king of Denmark, Norway and England.

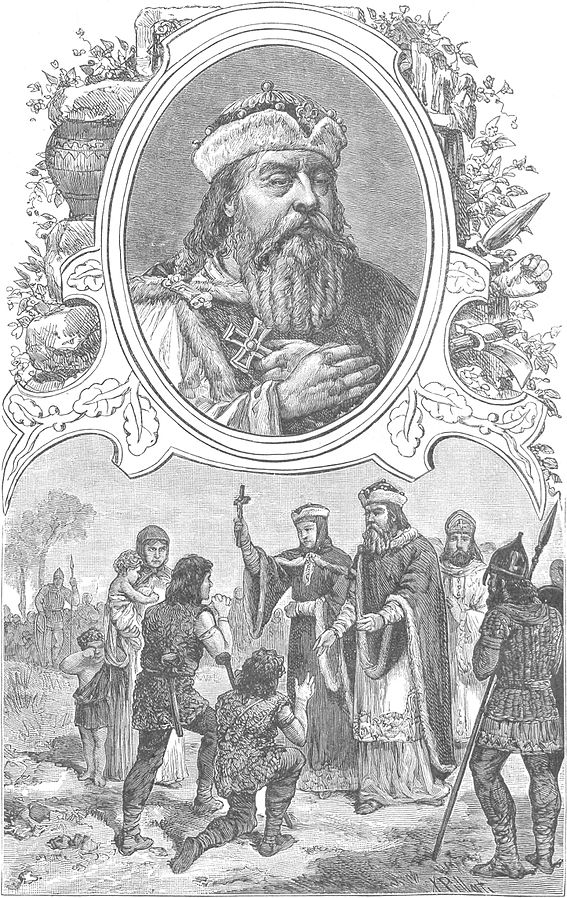

Cnut as he appears in E.S. Brooks’ Historic Boys

But the DANISH part of that description is not precisely accurate; because although Cnut’s father, Swein Forkbeard, was Danish, Cnut’s mum was a Polish princess. I hope you’re sitting down, because what I’m about to relate is complicated.

Historians agree that Cnut’s mum was the second wife of King Swein, but other than that she is shrouded in mystery. It’s not clear if Swein was her first husband or her second husband. It’s not clear when they were married, or where and when she gave birth to her children, or how many children she had. We’re not even certain of her name.

What we do know is that Cnut’s mother was the sister of Boleslaw the Brave, King of Poland…

Boleslaw Chobry. Wikimedia Commons

and that their parents were Mieszko of Bohemia of the Piast dynasty…

Mieszko. Wikimedia Commons

and a Bohemian princess named Doubravka who, through her marriage, brought Christianity to Poland.

Doubravka of Bohemia. Wikimedia Commons

Which means that Cnut’s mum was a Christian, and therefore her children, if they spent any time with their mother at all, would also have been Christian. Indeed, Cnut’s baptismal name was Lambert.

But what was Cnut’s mother’s name? Of that we can’t be sure. The names that have been suggested are Swietoslawa, Gunhild, and Sigrid. Professor Timothy Bolton in his recent biography of Cnut suggests that she was Swietoslawa, a name common in the Piast dynasty. The name appears Anglicized as Santslave in the Liber Vitae of New Minster, Winchester, in reference to a sister of Cnut who, it’s suggested, might have been named after her mother. Ian Howard, author of Swein Forkbeard’s Invasions, suggests that, whatever her birth name might have been, she was given the Scandinavian name Gunhild when she married Swein. This seems quite plausible, for it was not unusual for a woman to take a new name when she married into a new culture. Emma of Normandy, for example, was given the name Ælfgifu when she married the English King Æthelred, and sometimes both of her names, Ælfgifu Emma, appear in the records. Such may be the case with Swietoslawa Gunhild. But she’s also been identified with Sigrid the Haughty, a lusty queen who appears in the Norse sagas. More about her in a moment.

Ian Howard claims that Swein’s Polish wife with the new, Scandinavian name Gunhild, gave birth to two sons, Harald and Cnut, and possibly a daughter named Estrith, but he doesn’t attempt to suggest when or where her children were born. Presumably it was in Denmark in the late 980s because in 990, according to Howard, Swein and his family were driven out of Denmark by a Swedish army led by King Erik the Victorious. While Swein took to the seas—he was ravaging in England in 991 and 992—Gunhild fled to Pomerania (part of Poland) on the southern Baltic coast.

Swein eventually returned to Denmark when his Swedish enemy King Erik the Victorious died (in 993, 994, or 995—not sure) and was no longer a threat. According to Ian Howard, Swein ensured his sovereignty over Sweden by marrying Erik’s widow, Sigrid the Haughty, conveniently ignoring the fact that he had a wife in Pomerania. Sigrid, as described by James Reston, Jr. in The Last Apocalypse, was a lusty older matron with several grown children, who enjoyed the company of bawdy drinking men. She must have been a handful, even for Swein. According to Howard, Swein’s daughter Estrith might have been Gunhild’s daughter or she might have been the daughter of the bold Sigrid.

Sigrid the Haughty. From 1899 translation of Heimskringla, Wikimedia Commons

Professor Bolton, though, doesn’t accept the existence of Swein’s wife #3, Sigrid the Haughty. He suggests that Swein had only two wives. His first wife, name unknown, was the mother of Swein’s daughter Gytha, who all agree was Cnut’s elder half-sister. Swein’s second wife was the Polish sister of Boleslaw, and she, not the saga queen named Sigrid, was married first to the Swedish king Erik the Victorious, and after the death of her husband in 993, 994, or 995, she wed Swein. Her three children by Swein were Harald, Cnut and Estrith. If Bolton is right, all three of these children must have been born in the mid-to-late 990s, after the death of King Erik and Swein’s marriage to his widow, instead of the in the 980s, as Howard suggests.

But according to the Encomium Emmae Reginae, written at the behest of and with information provided by Cnut’s widow, Queen Emma, after Swein Forkbeard died in 1014 his sons Harald and Cnut went to “the land of the Slavs” and brought their mother back with them to Denmark, implying that at some point Cnut’s mother had left Denmark and been separated from her husband and sons. If this is true, Cnut and Harald must have spent enough time with their mother when they were children to have formed some filial attachment to her. In my mind that argues for a marriage to Swein in the 980s, per Howard’s thesis, not the 990s as Bolton suggests. Either way, though, her name probably wasn’t Sigrid.

So, was Swietoslawa/Gunhild, as Howard claims, Swein’s virginal young bride who gave him two sons and possibly a daughter in the 980s, only to be eventually set aside for the lusty Sigrid? Was she, as Bolton believes, the grieving Polish widow of a Swedish king, forced into marriage with Swein as one of the spoils of war, yet somehow confused with a character in the Norse sagas? And if she wasn’t the haughty, strong-minded Sigrid of the sagas, might she have had some of her characteristics?

The answer depends on whether your primary sources are the German chroniclers, the Icelandic Sagas, the Encomium Emmae Reginae, or some combination of them. Certainly, she was the sister of the Polish king Boleslaw the Brave. That much is clear. I’m inclined to think that her name was Swietoslawa, and that she took the name Gunhild upon her marriage to Swein in about 980, as Howard suggests. She gave Swein at least three children, but Swein eventually set her aside in the mid-990s, sending her back to ‘the land of the Slavs’ in order to make a political marriage to Sigrid, the widow of King Erik the Victorious. It’s the only way I can make all the names, the dates, and the relationships work out.

In my novel The Steel Beneath the Silk Cnut’s mother’s name is Gunhild, and as the dowager queen of Denmark and mother of its king, Harald, she is arrogant and domineering toward the other women at court. (Unconsciously, it seems, I allowed a little bit of Sigrid to leak into her character.) Cnut’s sister Estrith appears in the novel, too, as does their elder half-sister Gytha. Together with queen mother Gunhild, these three women are Cnut’s tall, formidable, flame-haired female kin.

Sources:

Bartlett, W. B. King Cnut and the Viking Conquest of England 1016. Amberley Publishing, 2016.

Bolton, Timothy. Cnut the Great. Yale University Press, 2017.

Howard, Ian. Swein Forbeard’s Invasions and the Danish Conquest of England, 991-1017. Boydell Press, 2003.

Reston, Jr., James. The Last Apocalypse: Europe at the Year 1000 A.D. Doubleday, 1998.

Sawyer, Peter. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Wikipedia: Swietoslawa of Poland.