I met author Jeri Westerson when she swept into my hometown a few years back to talk about history, mystery and her Medieval Noir hero Crispin Guest. She’s a terrific speaker and a talented mystery writer, and today I’m delighted to help celebrate the publication of her latest novel, SHADOW OF THE ALCHEMIST, by welcoming her as guest blogger. Her area of expertise is the High Middle Ages, but as you will see, she’s cannily worked in references to the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings and the Normans in this delightful and informative post. Here’s Jeri Westerson:

Why Can’t the English Teach Their Children How to Speak?

by Jeri Westerson

You might recognize the title of this blog post from the musical “My Fair Lady” wherein linguist Henry Higgins laments that the English language was being corrupted by its many dialects. Indeed, George Bernard Shaw, who penned the original play “Pygmalion” on which “My Fair Lady” was based, was supposed to have said, “The English and the Americans are two peoples divided by a common language.” Even better, James D. Nicoll, fiction reviewer, among other things, claims, “The problem with defending the purity of the English language is that English is about as pure as a cribhouse whore. We don’t just borrow words; on occasion, English has pursued other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary.”

Now you would think that the English people would be speaking, well, English. But London of the 1300’s saw an interesting change. Yes, it was English but English of a sort. We call it Middle English. But we’re going to need to back up a lot farther than that.

Before the Romans came to Britain in AD 43, there were already diverse and thriving tribes populating the island. The Picts in Scotland, the lowlander tribes of England (that went by many names), and the dwellers of Wales. To use the term “Celts” is out of date. An eighteenth century invention, the notion of “Celts” was a Gallic, that is to say, French ethnic label. In Iron Age Britain they never called themselves “Celts.”

When the Romans invaded, they shared a few genes with the locals but also a bit of Latin to the varied languages already evident in England. Remember, the Roman Empire sort of gave up at the Scottish border and Emperor Hadrian built a rambling wall to keep the barbarians out. What remains of that wall still survives in the English countryside.

When the Romans were finally repelled in the fifth century and when Christianity was taking hold, monks came to Ireland and trickled down through England, bringing more Latin and Greek. But things really started to change when one of the kings of the Britons needed help with those pesky Picts to the north and invited the Angles and the Saxons—fellows from Germany—to help out. Perhaps not the wisest of moves, for who was now going to get rid of those guys? But now we have German coming into the mix of Gaelic and Latin. Meanwhile, the Vikings kept striking, leaving a bit of Danish in their wake. The language, not the pastry. The “English” language is now a complete mess. Now do you understand why we have words with letters that are silent and some that make no sense at all? But wait, it gets better.

While the original languages of Britain still flourished in Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall, the rest of England (that’s Angle-land, they even took over the name of the place! Pesky Germans.) was now speaking a form of English we call Old English or Anglo-Saxon, the stuff that Beowulf was speaking when he wasn’t busy hacking at monsters.

By the time the Anglo-Saxons were well established (and the occasional Danish Viking kept invading), another threat to hearth, home, and language came to English shores by way of France. Normandy to be exact, in the person of William the Conqueror, known on the continent as duke William of Normandy or just William the Bastard. He says he was invited. The Anglo-Saxons said, “William who?” He came anyway and with an army to take the crown that he believed Edward the Confessor said he could have. And when he crowned himself King of England in Westminster Abbey and replaced the Anglo-Saxon nobles with his Norman ones, a new language invaded. Medieval French! Now we’re really mixing it up.

And for a very long time, anybody who was anybody in England would be speaking French as France and England had close ties. In the twelfth century, King Richard I, also known as the Lionheart, didn’t speak English at all and didn’t spend more than six months in his entire life in England. But this exclusive use of French by the nobility slowly began to change as did the relationship with France.

By the time we reach King Richard II’s England in my own novels (1380’s) the crossover of all these languages—Latin, Greek, German, Danish, French, with a smattering of the native languages from Wales, Scotland, and Ireland—had been put in a blender and switched on high. Everyone is now speaking what we call Middle English. And this was an important period, because no longer are the nobility so out of touch (at least in terms of language) with the general population, because for the first time, they are also speaking English. Middle English, but still English. Is this an English we can understand? Well, not so much. It’s much easier to read it on the page, than to hear it. And there was good stuff to read. This is the era of Geoffrey Chaucer and he was important because, also for the first time, poetry and popular literature like THE CANTERBURY TALES, is being written not in French as was the style, but in English. What a modern day person probably couldn’t do—and I even have a hard time—is understanding it when it is spoken. Remember all those silent letters we have in words? Well, they weren’t silent then. Middle English, like German, was phonetic, that is, each letter was pronounced. In the word “Knight” for instance, we pronounce it as “nite” but in Middle English you pronounce each letter—K-N-EE-CH-T—with a guttural chicken-bone-in-the-throat thing for the “CH.”

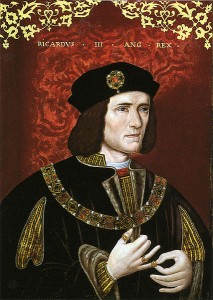

And by the time we reach about Richard III’s day (fifteenth century), they are speaking a recognizable English right through to Elizabethan/Shakespearean (sixteenth century) English, the real precursor to modern English.

What’s next for English? If texting is any indication, we’re in big trouble.

—-

Jeri tries to stay out of as much trouble as she can by putting her medieval detective Crispin Guest in all kinds of danger. Her books have garnered nominations for the Shamus, the Macavity, the Agatha, Romantic Times Reviewer’s Choice, and the Bruce Alexander Historical Mystery Award. She is president of the southern California chapter of Mystery Writers of America and is vice president of the Los Angeles chapter of Sisters in Crime. When not writing, Jeri dabbles in gourmet cooking, drinks fine wines, eats cheap chocolate, and swoons over anything British. (I happen to know that she is passionate about mead.) Her latest Medieval Noir novel, SHADOW OF THE ALCHEMIST is now in bookstores. For more info—including book discussion guides—go to her website www.JeriWesterson.com