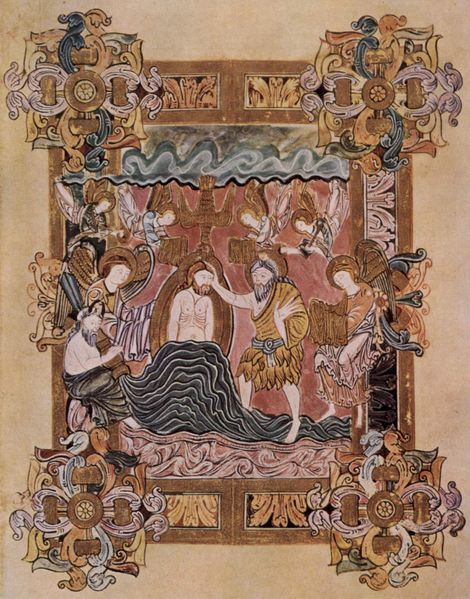

King Æthelred II, from The Life of King Edward the Confssor. 13th c. Cambridge University Library (Wikimedia Commons)

On 23 April 1016, King Æthelred II died in London. He was about 50 years old, and he’d ruled England for 38 years. At his death he’d not yet been given the byname, Unræd, (ill-counseled, a play on the Old English meaning of his name, æthel ræd – noble counsel). That would come some years later. Eventually Unræd would be corrupted into Unready, and he would be known as Æthelred the Unready for centuries. As the bynames suggest, his reputation has been anything but enviable:

“His life is said to have been cruel at the outset, pitiable in mid-course, and disgraceful in its ending.” William of Malmesbury, History of the English Kings, 12th century;

“He is the only ruler of the male line of Ecbert whom we can unhesitatingly set down as a bad man and a bad king.” Edward Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, 1867;

“Good reputations rarely befall those who live for a long time… Had he died in the early years of the 11th century, then we might well remember a king of some competence…” Ryan Lavelle, Æthelred II, 2004.

Talk about damning with faint praise: If only Æthelred had died abruptly at age 34, as his father Edgar did, the 11th century might have been easier for the English. The infamous St. Brice’s Day Massacre of Danes in 1003 would never have happened; nor the debilitating taxation that oppressed the English people and enriched many a Viking; nor Æthelred’s humiliating abdication to a Danish warrior king; nor even that battle at Hastings in 1066 that opened the door to centuries of Norman rule. Æthelred, it seems, has a lot to answer for.

But what do we really know about the man himself? Biographer Ann Williams, in Æthelred the Unready, the Ill-counselled King, cautions: “We do not and cannot know what kind of a man Æthelred was, only what he did and what happened to him.”

Williams may be right, but as a novelist writing about Æthelred’s reign I needed to decide what kind of a man Æthelred was. I had to study what he did, what happened to him, and then I had to make up my mind about him. Truth be told, I was hoping to find a villain. And indeed, this ruthless, vindictive, sometimes energetic, sometimes irresolute king (one historian refers to his reign as bi-polar) was the answer to my prayers.

Æthelred came to the throne under a cloud of suspicion and foreboding – and that’s not something I made up. His half-brother, King Edward, had been brutally murdered, and that crime paved the way for Æthelred’s coronation. That no one was punished for King Edward’s murder hints at a cover-up, if not collusion, by someone in power; if not the new young King Æthelred, aged ten, then others quite close to him. His reputation as ill-counselled had already begun.

William of Malmesbury wrote that Æthelred was haunted by the shade of his brother, demanding terribly the price of blood. That single phrase inspired my creation of a ghost that torments the beleaguered king in my novels. And because contemporary accounts describe King Edward as violent even toward his own supporters, the ghost that I’ve created is no mild-mannered martyr.

The air before him thickened and turned as black and rippling as the windswept surface of a mere. Pain gnawed at his chest, and he shivered with cold and apprehension as the world around him vanished. Sounds, too, faded to nothing and he knew only the cold, the pain, and the flickering darkness before him that stretched and grew into the shape of a man. Or what had been a man once. Wounds gaped like a dozen mouths at throat and breast, gore streaked the shredded garments crimson, and the menacing face wore Death’s gruesome pallor. His murdered brother’s shade drew toward him, an exhalation from the gates of heaven or the mouth of hell – he could not say which. Not a word passed its lips, but he sensed a malevolence that flowed from the dead to the living, and he shrank back in fear and loathing. from THE PRICE OF BLOOD

Edward’s ghost is my way of explaining the sometimes baffling decisions that Æthelred made. Truly, there were times when, as I conducted my research, I exclaimed, “But why would you do that?”

There is no question that there were political, social, and religious complexities to Æthelred’s long reign, not to mention recurring Viking attacks and an endless string of dire events that can only be characterized as rotten luck, and I’ve tried to reflect these in my books. But the shorthand for how the king responded to catastrophe is expressed by the appearance of his brother’s ghost. (Thank you, St. Edward the Martyr!)

Was the historical figure of Æthelred, though, any more ruthless or paranoid than other rulers of his time? I doubt it. His was a world that was governed by the sword despite the laws that he enacted and presumably sought to enforce. He ruled a newly united England in which allegiances to kin were far stronger than any oaths made to a distant king, so Æthelred had good reason to be suspicious of the men around him. In the final, dark years of his reign, with a Viking army ravaging the land, all loyalties were strained to the breaking point, and English unity fractured. “…there was not a chief that would collect an army, but each fled as he could: no shire, moreover, would stand by another.” (The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle)

Nevertheless, Æthelred’s success at holding his kingdom together for over 30 years meant that art and culture could flourish despite the unrest that plagued England. Benedictine abbeys patronized by wealthy nobles produced gloriously illuminated manuscripts, metalwork, and sculptures.

Many of the greatest works of Old English literature were written at this time including lives of saints and the homilies of Ælfric and of scholar/statesman Archbishop Wulfstan. The only copy of Beowulf in existence was produced, it’s believed, while Æthelred was king (although recently some scholars think it was later, but that’s another blog post).

Such accomplishments as these, though, must be weighed against murders, executions, misplaced trust, bad decisions and desperation that characterized his reign. Æthelred died a king, but he was a king who was ill-equipped to cope with the enormous challenges he faced. Even if he was not literally haunted by his brother’s ghost, he must have been, in his final days, haunted by his failures as a ruler.

“He ended his days on St. George’s day; having held his kingdom in much tribulation and difficulty as long as his life continued.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 11th century