Today, the chalk hill of Corfe on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset is crowned by the ruins of, for the most part, a 12th century Norman castle. But in Anglo-Saxon times a hunting lodge stood on the hill, and the story of what happened there on 18 March, 978, has been elaborately embroidered over the centuries.

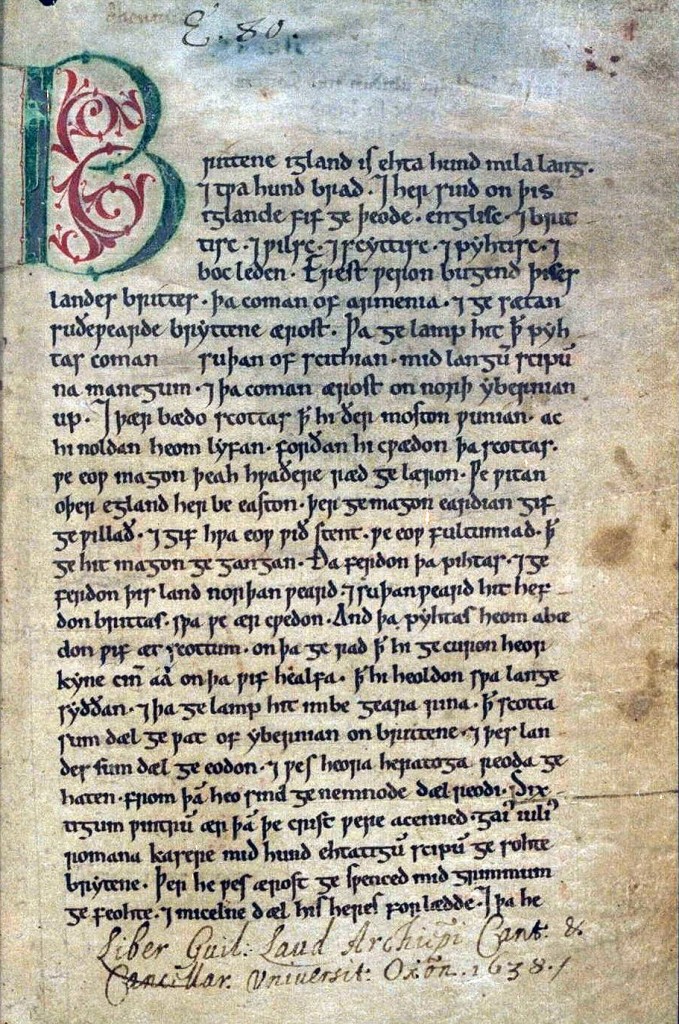

The first account appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

“This year was King Edward slain, at eventide, at Corfe-gate, on the fifteenth day before the calends of April. And he was buried at Wareham without any royal honour. No worse deed than this was ever done by the English nation since they first sought the land of Britain.” (1)

After Edward’s death, his 10-year-old half-brother, Æthelred II, took the throne, and the Chronicle account quoted above may have been written during Æthelred’s lifetime. Note that there is no mention of how Edward was slain, or of who did it, specifically, although the murder appears to be laid at the feet of the entire English nation, which I find pretty interesting. Remember, the Viking raids began soon after this, and they were thought to be punishment for the sins of the people of England. Did that include the murder of a king?

An account in the Vita S. Oswaldi written about the year 1000 adds that Edward had gone to Corfe to visit his half-brother who was staying with his mother, and that certain zealous thegns of Æthelred’s killed him. (2) We’re also given a picture of the young King Edward’s personality when the writer claims that Edward inspired terror in all because he scourged them with words and even blows. (3)

An account in the Vita S. Oswaldi written about the year 1000 adds that Edward had gone to Corfe to visit his half-brother who was staying with his mother, and that certain zealous thegns of Æthelred’s killed him. (2) We’re also given a picture of the young King Edward’s personality when the writer claims that Edward inspired terror in all because he scourged them with words and even blows. (3)

Written in the late 11th century, The Passio S. Eadwardi, adds the detail that Edward’s stepmother, Queen Ælfthryth, actually plotted the killing so that her son Æthelred could be king. (2)

So, within 100 years of the incident, a picture is beginning to emerge of a disputed succession that ended in a brutal murder planned by Æthelred’s mother. In the 12th century, chronicler William of Malmesbury elaborately embroidered the tale:

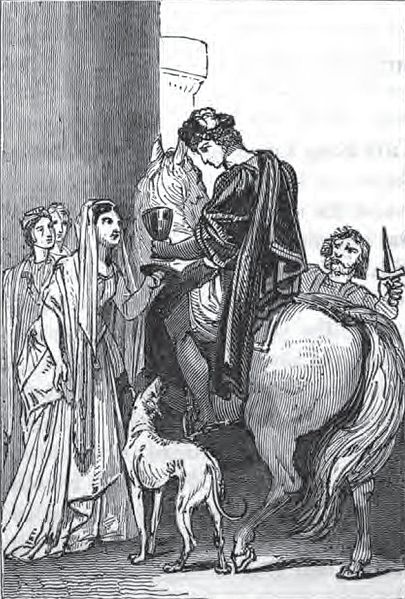

“The woman however, with a stepmother’s hatred and a viper’s guile, in her anxiety that her son should also enjoy the title of king, laid plots against her stepson’s life, which she carried out as follows. He was coming back tired from hunting, breathless and thirsty from his exertions; his companions were following the hounds where chance had led each one; and hearing that they were quartered in a neighbouring village, the young man spurred his horse and hastened to join them, all by himself, too innocent to have any fears and no doubt judging other people by himself. On his arrival, his stepmother, with a woman’s wiles, distracted his attention, and with a kiss of welcome offered him a drink. As he greedily drank it, she had him pierced with a dagger by one of her servants. Wounded mortally by the blow, he summoned up what breath he had left, and spurred his horse to join the rest of the party; but one foot slipped, and he was dragged through byways by the other, leaving streams of blood as a clear indication of his death to those who looked for him. At the time they ordered him to be buried without honour at Wareham, grudging him consecrated ground when he was dead, as they had grudged him the royal title while he was alive.” (3)

“The woman however, with a stepmother’s hatred and a viper’s guile, in her anxiety that her son should also enjoy the title of king, laid plots against her stepson’s life, which she carried out as follows. He was coming back tired from hunting, breathless and thirsty from his exertions; his companions were following the hounds where chance had led each one; and hearing that they were quartered in a neighbouring village, the young man spurred his horse and hastened to join them, all by himself, too innocent to have any fears and no doubt judging other people by himself. On his arrival, his stepmother, with a woman’s wiles, distracted his attention, and with a kiss of welcome offered him a drink. As he greedily drank it, she had him pierced with a dagger by one of her servants. Wounded mortally by the blow, he summoned up what breath he had left, and spurred his horse to join the rest of the party; but one foot slipped, and he was dragged through byways by the other, leaving streams of blood as a clear indication of his death to those who looked for him. At the time they ordered him to be buried without honour at Wareham, grudging him consecrated ground when he was dead, as they had grudged him the royal title while he was alive.” (3)

Now we have a full-blown, bloody scenario with a tragic, innocent young king, a wicked stepmother, Biblical allusions (a viper’s guile; a kiss of betrayal), a single murderer with a knife, and a pitiful, wounded victim trying to reach help to no avail. Wow. William could be a script writer for Game of Thrones.

William claimed that his History was based on earlier sources (now lost), as well as whatever version of

the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle he had there at his abbey in Malmesbury. It was a famed center of learning in the Anglo-Saxon period, so it’s possible that William had access to many resources that have since been lost. (Thank you, Henry VIII.)

Some scholars, though, believe that William’s scurrilous portrayal of Queen Æfthryth is a reflection of events happening in Britain at the time William was writing his Chronicle. Henry I was on the throne then, but his only son was dead. The men of England were faced with the possibility of a woman succeeding to the throne, and that wasn’t sitting well with a lot of them. There were grave concerns about powerful women being in charge of the kingdom. At about this same time other sources vilify Queen Ælfthryth as lustful, a witch who dabbled in poisons, and a shape shifter, as well as the original wicked stepmother.

So, what is the truth? What do we know for certain, and what can be conjectured from the historical documents?

1. There was a significant faction that had wanted Æthelred, not Edward, to be named king. This same group was disgruntled by Edward’s actions once he had the throne.

2. Edward was murdered, and there was probably at least one knife involved.

3. His body was thrown into a nearby well, then moved to Wareham. Finally he was reburied with great honor at Shaftesbury Abbey, but not until after Queen Ælfthryth was dead.

4. No one was ever punished for the murder of the young king.

It may be that Edward’s death was unplanned, that it was the result of an argument spinning out of control. My own thinking, though, is that the queen had some involvement in his murder. There is just too much smoke for there not to be a flame at the heart of it, and the fact that no one was punished for the crime lends credence to the theory that the queen played some role. At the very least, she was there. Even young Æthelred was there somewhere, and who can say what he saw and heard, if anything? The murder may have been unintentional, a matter of an offhand remark, like Henry II’s ‘Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” But if Edward was the arrogant, cruel young man described in the Vita S. Oswaldi, there may very well have been a plot to rid England of an obnoxious young punk of a ruler and replace him with someone more pliant. (Anyone who knows the history of Æthelred’s reign knows that this did not turn out well.)

In my novels Shadow on the Crown and The Price of Blood, (following the suggestion of our favorite storyteller historian William of Malmesbury who writes that Æthelred was hounded by the shade of the murdered Edward), a guilt-ridden Æthelred is haunted by his brother’s wraith. Whatever the truth of Edward’s murder – and it remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the Anglo-Saxon period – his death was a stain on Æthelred’s reign that he was never able to erase.

(1) www.britannia.com/history/docs/973-79.html

(2) The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, Ed. Michael Lapidge, Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

(3) English Historical Documents, 500-2042, ed. Dorothy Whitelock, Routledge, 1996.

(4) The History of the English Kings by William of Malmesbury, edited & translated by R.A.B. Mynors, R. M. Thomson & M. Winterbottom, Volume 1 (1998), Oxford University Press.

Fantastic post. When I visited Corfe I was imagining Edward’s murder and also the poor French knights that King John had sent there.

Our guide told us that the place was haunted. I couldn’t say whose ghost it might be, but there are plenty to choose from.

It’s one of the best unsolved murder mysteries that doesn’t get enough credit or attention. When one adds in the ghosts and the hauntings of Athelred it becomes even better!

What is sad is how much written history has been lost over the centuries due to those like Henry VIII, or due to unknowing and wanton destruction such as the Viking raiders caused with their assumptions that those words were unimportant at the time.

This mystery also points out the problem of who to believe in historical accounts- or any accounts of an event? It’s one of those cases of unless we were there and actually witnessed the events, we will never be sure of what really happened or why? And, even if we had been there, we would each recount or remember the event with a slightly different perspective.

It’s true life mysteries like this one that I love reading about from all of those different perspectives of what might have happened or why it happened!

Hi Judy. You’re right, the further into the past we look, the foggier it gets. And it’s those gaps in our knowledge – those mysteries – that make historical fiction so much fun to read and to write. Authors have to do the research, of course, and explore all the different theories about what took place, and that’s a fascinating endeavor, too. The historical novelist owes a very great deal to the scholars who do all the in-depth research that makes our flights of imagination possible.

You may wish to bear in mind that the ‘Passio’ only survives in post-Conquest manuscripts and is now thought to have been written in the late (rather than early) eleventh century, perahps by Goscelin of St-Bertin. This substantially changes the picture, leaving us with no pre-Conquest (or even near contemporary) source implicating Ælfthryth. Of course, it’s hard to prove a negative, but I’d be wary of using the ‘no smoke without fire’ argument under such circumstances.

Thank you, Professor Roach, for pointing out my error about the date of the Passio – which was, indeed, my error. My source says late 11th century, and I missed that. I have corrected it in my post. I believe most scholars today probably agree with Sean Miller’s assessment in Blackwell’s that “without earlier evidence it is simplest to assume that Aethelred’s zealous thegns acted on their own initiative, perhaps expecting more advancement under Aethelred.” This entire incident may be an excellent example of the vilification of the reputation of a powerful woman following bitter court rivalry between nobles, churchmen, & family. Rachel Anderson, in a paper she gave at Kalamazoo in 2012, made a strong case for the queen’s innocence. Still, in Unification & Conquest Professor Stafford writes of Aelfthryth, “The forms of political action open to women were limited to the intrigues of court, survival in that world their only hope. If we cannot know whether she planned the murder, it is certain that she benefited from it.” I hope I made clear that I was expressing my own personal opinion on the queen’s involvement. I have to plead guilty to viewing it with a novelist’s gimlet eye rather than the more sober, objective gaze of a scholar and historian.

To be fair, I doubt it’s really ‘your’ error – much of the earlier literature presumed that the later Passio was based on an earlier one of c. 1001 and it’s only recently that the matter has (to my eyes) been definitely settled. In any case, it’s wonderful to have a novelist working on the period who cares so much for such (relatively minor) points of detail!

I’m enormously grateful for the help and encouragement I’ve received from the academic community. On a final note regarding Aelfthryth, another novelist has taken a long look at the queen in a recent book that I have not yet read. Elizabeth Norton’s ELFRIDA has her as the central figure. I’m very curious to see how she deals with the events at Corfe!