Today I am delighted to welcome historical novelist Elisabeth Storrs, author of the Tales of Ancient Rome saga – three novels set in the late 4th century BC.

Today I am delighted to welcome historical novelist Elisabeth Storrs, author of the Tales of Ancient Rome saga – three novels set in the late 4th century BC.

A graduate of Arts Law from the University of Sydney where she studied the Classics, Elisabeth’s inspiration for her novels was a sarcophagus that depicted a couple embracing for eternity. The casket was unusual because in this period of history, women were rarely commemorated in funerary art let alone in such a pose of affection. Her interest piqued, the research began. Eventually, Elisabeth’s discovery of a little-known story about the struggle between the Etruscan city of Veii and Republican Rome led to her penning of the Tales of Ancient Rome Saga, novels that immerse readers into a complex, ancient world filled with drama, love, loss and heroism. Now, here is Elisabeth, to tell you more.

One of the main themes in my Tales of Ancient Rome saga is an exploration of the lives of women in the ancient world through the portrayal of female characters from different cultures: a Roman bride (Caecilia), Roman prostitute (Pinna), Greek slave (Cytheris), Cretan courtesan (Erene), and also three Etruscan women: the aristocratic matrons Larthia and Ramutha, and lastly, the artisan (turned wet nurse), Semni.

One of the main themes in my Tales of Ancient Rome saga is an exploration of the lives of women in the ancient world through the portrayal of female characters from different cultures: a Roman bride (Caecilia), Roman prostitute (Pinna), Greek slave (Cytheris), Cretan courtesan (Erene), and also three Etruscan women: the aristocratic matrons Larthia and Ramutha, and lastly, the artisan (turned wet nurse), Semni.

What was the status and role of women in classical times? In both Greece and Rome they were chattels possessed by men. Athenian women were cloistered within women’s quarters and were restricted to household duties. In Rome they were second class citizens without the right to vote or hold property. Further, Roman women rarely ate with their men and could be killed with impunity by their husbands or fathers for adultery or drinking wine.

In early Roman and Greek cultures a woman’s primary purpose was to bear children in order to ensure the continuation of her husband’s bloodline. Their identities were defined by their relationship as either daughter or wife. Roman women were only known by one name, that of their father’s surname in feminine form. In death their remains were placed in a man’s tomb and they were not publicly commemorated. However, while Roman and Greek wives weren’t given the opportunity for education and social freedom – in Athens, courtesans were. These hetaerae “companions” were allowed to dine with men and drink wine at banquets while discussing politics, philosophy, literature and enjoying entertainments. Of course, they also provided sexual favours to the patrons who owned them.

In comparison, Etruscan women were afforded independence and education. They could share their husband’s dining couch and drink wine. They had two names denoting both paternal and maternal bloodlines. Some accounts also state that wives had sexual freedom and may even have been able to claim their illegitimate children in their own right. Also intriguing is historical evidence that high born women held positions as priestesses.

One famous Etruscan priestess, according to the historian Livy, was a seer named Tanaquil (Tanchvil in Etruscan). According to legend, her positive interpretation of an incident in which an eagle snatched her husband’s cap, then swooped down to replace it on his head, persuaded Tarquinius Priscus to go to Rome where he eventually become the first king of the Tarquinian Etruscan dynasty. As such Tanaquil was traditionally believed to be the “power behind the throne.”

So could the myth of a prophetess such as Tanaquil be based in fact? The Etruscans were indeed skilled in the art of foretelling the future from the flight of birds. And there is evidence from funerary art that women may well have been priestesses of high standing. The Tomb of Inscriptions is one such example. Members of several families were buried within its six chambers. Two of the ladies were designated as ‘hatrencu’. Extraordinarily, the women were not laid to rest beside their husbands and children which was usually the rule in Etruria for female burials in family tombs. Instead they lay in the company of women with different family names but bearing the same title of ‘hatrencu’. This collegial link has been persuasively argued as proving ‘hatrencu’ referred to a member of a priestly college concerned with a female cult dedicated to fertility and marriage.

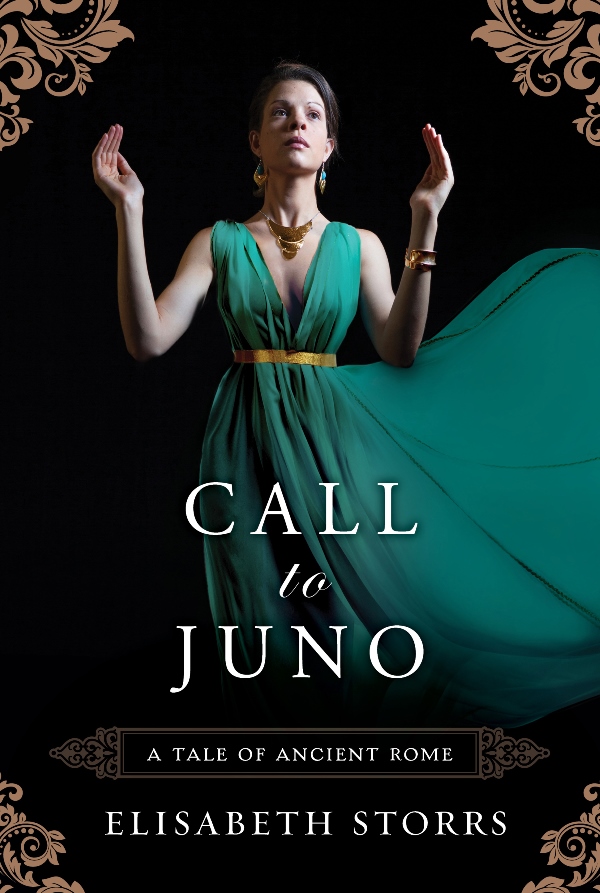

In my latest novel, Call to Juno, I have introduced a new female character who melds the legend of Tanaquil with the hatrencu buried in the Tomb of Inscriptions. She is Tanchvil, the high priestess of the Temple of Uni, who like the mythical Tanaquil divines the future from the flight of an eagle, Antar.

Tanchvil carefully removed the hood. The eagle’s head and breast were flecked with gold, his dark plumage shiny. If he chose to flap his enormous wings he could break free even before his mistress had loosened the leather restraints. And what was to prevent him from turning and ripping her face with his beak?

The hatrencu lifted her arm to send Antar skyward. Caecilia felt the swish of air as the eagle rose, his pinions extended, seeking the thermals. Holding her breath, she waited to see to which quadrant of the heavens he would fly. His wings stretched in perfect symmetry; the raptor spiraled higher, gliding over the southeast of the city before heading northeast. Then he hovered for a moment before diving and swooping upward again.

A strong thread exploring the concepts of fate versus freewill is woven throughout The Wedding Shroud and The Golden Dice, the first two books in the Tales of Ancient Rome saga. The theme continues in Call to Juno. Tanchvil’s role is crucial in prophesying the fate of Veii in the final year of its ten year struggle with Rome. The hatrencu warns Queen Caecilia and King Mastarna to be wary of the fickleness of Uni, their city’s regal goddess. For the Romans also worship her and seek to entice her to forsake Veii and take up residence in Rome as Juno the Queen. Both enemies call to Juno Regina to favor their cities. What destiny lies in store for them?

Praise for Call to Juno: A Tale of Ancient Rome by Elisabeth Storrs

Praise for Call to Juno: A Tale of Ancient Rome by Elisabeth Storrs

“An elegant, impeccably researched exploration of early Rome and their lesser known enemies, the Etruscans. The torments of war, love, family, and faith are explored by narrators on both sides of the conflict as their cities rush toward a shattering, heart-wrenching show-down. Elisabeth Storrs weaves a wonderful tale!” Kate Quinn, author of The Empress of Rome Saga

About Call to Juno:

Four unforgettable characters are tested during a war between Rome and Etruscan Veii.

Caecilia has long been torn between her birthplace of Rome and her adopted city of Veii. Yet faced with mounting danger to her husband, children, and Etruscan freedoms, will her call to destroy Rome succeed?

Pinna has clawed her way from prostitute to the concubine of the Roman general Camillus. Deeply in love, can she exert her own power to survive the threat of exposure by those who know her sordid past?

Semni, a servant, seeks forgiveness for a past betrayal. Will she redeem herself so she can marry the man she loves?

Marcus, a Roman tribune, is tormented by unrequited love for another soldier. Can he find strength to choose between his cousin Caecilia and his fidelity to Rome?

Who will overcome the treachery of mortals and gods?

Elisabeth Storrs lives with her husband and two sons in Sydney, and over the years has worked as a solicitor, corporate lawyer and corporate governance consultant. She is the Deputy Chair of the NSW Writers’ Centre and one of the founders of the Historical Novel Society Australasia.

Call to Juno: http://www.elisabethstorrs.com/buy-books/call-to-juno.html

Website: www.elisabethstorrs.com

Triclinium blog: www.elisabethstorrs.com.blog

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/elisabeth.storrs/

Twitter https://twitter.com/elisabethstorrs

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/elisabethstorrs/