Emma,

a gem more splendid through the splendors of her merits…

So begins the epigram written late in the 11th century by Godfrey, prior of Winchester, commemorating Emma, Queen of England.

Queen Emma died on 6 March, 1052, and was buried with great honor in the royal mausoleum, the Old Minster, in Winchester. Her passing was noted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and commemorated annually by prayers at Winchester’s New Minster, at Ely Abbey and at Christ Church Canterbury. At her death she was at least 60 years old, perhaps as old as 70, and for 32 of those years she was a queen of England. She was the consort of two kings, the mother of two kings, and the great-aunt of William the Conqueror who would have had no claim to the English throne in 1066 if it hadn’t been for Queen Emma. She was wife, mother, queen, widow and dowager queen through one of the most turbulent periods in England’s history.

Although Emma does not have the name recognition today of, say, Eleanor of Aquitaine or Ann Boleyn, she was a remarkable woman and quite well known, not only in her lifetime but for centuries after her death. Where’s the proof of that? Well, to begin with, we have two contemporary drawings of Emma – and that in itself is remarkable.

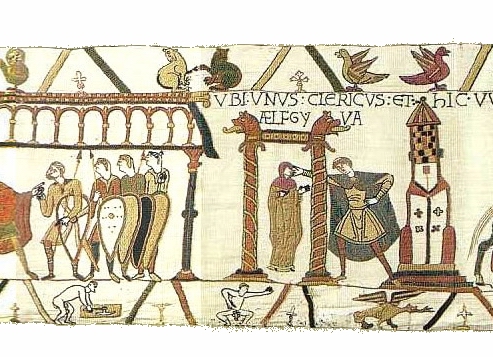

In addition, Emma, who was given the name of a royal Anglo-Saxon saint, Ælfgiva, upon her marriage to England’s King Æthelred, may be one of the few female figures stitched into the Bayeux Tapestry. Caveat: it is not certain that this is Emma. Scholars continue to argue passionately about the identity of the lady in the tapestry; she was important enough to be named, and apparently she was so well known at the time that anyone looking at the tapestry would have known who this Ælfgiva was and where she fit into the story. Not so those of us looking back at it from a distance of 900 years! The images surrounding her–the monk who reaches toward her face, and the little naked man in the lower border–merely add to the mystery.

Bayeux Tapestry, AElfgyva. Image on web site of Ulrich Harsh. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

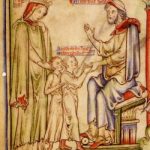

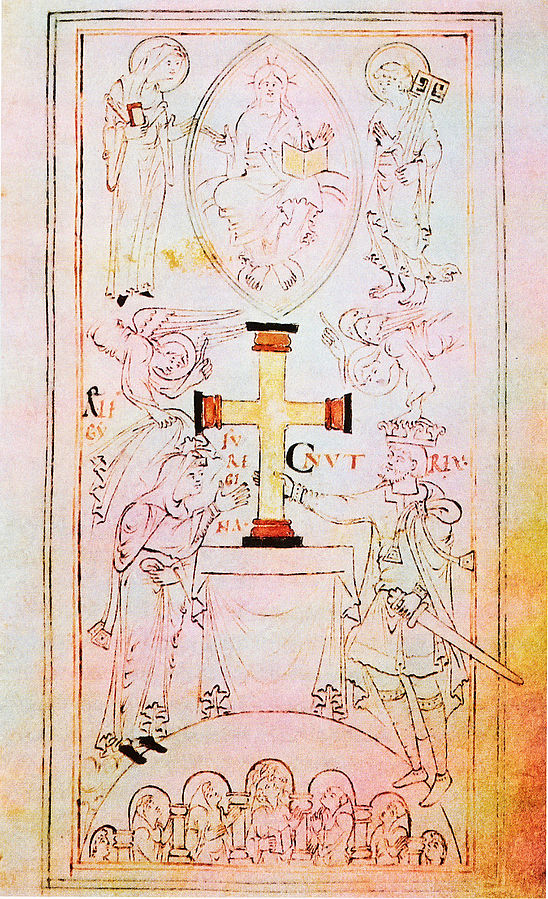

We are on much firmer ground some 100 years after Emma’s death when an anonymous artist depicted her in a lavishly illustrated, 12th century biography of her son, King Edward the Confessor.

Queen Emma presents her sons to Richard of Normandy, The Life of Edward the Confessor, 12th c., Cambridge University Library, Ee.3.59:fol4v

There are textual references to Emma, too, from the 11th century on. She appears in one of the Norse sagas, (Liðsmannaflokkr), as the chaste widow who stands upon the wall of London and watches the battle raging below her. She is mentioned in the annals of Germany and Normandy, and in the post-Conquest histories of England.

Late in her life Emma herself commissioned a book to be written about events she witnessed or which impacted her in some way. Known today as the Encomium Emmae Reginae, it was certainly read and discussed at the Anglo-Danish-Norman court where she reigned as queen mother. More than 500 years later a copy of that book was in the library of William Cecil, chief adviser to Elizabeth I, so it’s quite possible that the great Tudor queen, too, was familiar with Emma’s name and reputation.

Certainly someone in Elizabethan London knew about Emma. She appears as a character in a drama from that period titled Edmund Ironside. It’s not a very good play, although at least one scholar thinks it may have been a very early work of Shakespeare. Whoever the author was, he knew enough about Emma to imagine her as a queen and as a grieving mother who is forced to send her children out of England for their safety.

After that, we have to fast-forward to the 1960’s to find Emma again. In his 1968 production The Ceremony of Innocence, playwright Ronald Ribman imagined Queen Emma as, well, something of a harridan. He places her opposite an agonized and irresolute King Æthelred.

A very snarky Queen Emma in A Ceremony of Innocence.

It was at about that same time that historical novelists began to set their stories in 11th century England, and Emma was cast in supporting roles. You can find her in Anya Seton’s Avalon, Dorothy Dunnett’s King Hereafter, Helen Hollick’s I am the Chosen King, and Justin Hill’s Shieldwall.

Scholars of medieval history, of course, have always known about Queen Emma. Many eminent historians – Alistair Campbell, Helen Damico, Simon Keynes, Eleanor Searle, and, especially Pauline Stafford (Queen Emma & Queen Edith: Queenship & Women’s Power in 11th Century England, 1997) – have looked closely at Emma’s career. Their in-depth studies led to the publication of popular biographies by Isabella Strachan (2004) and Harriet O’Brien (2005).

In 2005, though, Emma was finally given a central role in a historical novel. Helen Hollick’s A Hollow Crown was published in England in that year, and it appeared in the U.S. in 2010 as The Forever Queen. Emma was making a comeback!

My own novel about Emma, Shadow on the Crown, was published in 2013. It has since been translated into four languages, introducing Queen Emma to readers in Russia, Germany, Italy and even Brazil. The sequel, The Price of Blood, was released in 2015, and it continues Emma’s story up to the year 1012. I am currently at work on the final book of the trilogy that will follow Emma into her second royal marriage and introduce her, I hope, to an even broader audience.

Recently, Queen Emma became the subject of scientific investigation. Her skeletal remains and those of a number of early English monarchs have for some years been undergoing examination by a team of scientists from the University of Bristol. The effort hopes to separate and identify bones that were tumbled together into mortuary chests in the 17th century, as well as to learn details about these long-dead royals. (Personally, I would love to know, at the very least, how tall Emma was and what her diet might have been.) Recently the Dean and the Chapter of the cathedral announced that the remains had been “formally dated by the Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at the University of Oxford and that their origins are thought to be from the late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman periods, which is consistent with the historical burial records of the named individuals.” The study is on-going, and I am sure that I am not the only one anxiously awaiting further announcements about their findings.

The mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral.

So, through the efforts of scientists, of scholars, of historians, of novelists who love history, and of readers who love historical fiction, this remarkable woman is once more garnering some name recognition as a significant figure in English history.

Shadow on the Crown, Russian edition.

Thank you, a great read and although I learned about this Queen in History, you have brought her alive, can’t wait for the final. Happy writing.

Karen

Thank you Karen!

Fascinating article, thank you. I didn’t know about the bones, hope to hear more.

I loved the story of Emma and am anxiously awaiting the continuation of this trilogy! Loved learning about Emma.

Hello! I’d like to know if the second book of the trilogy Will be publish in Brazil…

Hello Ines. I wish I had an answer for you, but I do not. My hope is that when I’ve finished the final book Arqueiro will publish the trilogy in Brazil, but it is something over which I have no control.

My symphony no. 20 “Queen Emma” is now completed. The movements include musical pictures of Emma and her children, the Vikings and of her death. The score is held in the printed music section of the British Library and in the library of the British Music Society. A software playback recording will soon be available on YouTube.

In my years-long sojourn with Queen Emma I have been privileged to make many wonderful acquaintances–readers, writers, scholars, historians, librarians, book shop owners, and now, a composer and, I understand, a paleontologist. (!!!!!) Heartiest congratulations, Doctor Blows, on your accomplishments, especially your symphony, “Queen Emma”. I am curious to know how you discovered this relatively little-known queen, and what sources you used in researching her life.

I am about half way through the first book and thoroughly enjoying it, not least because of its historical accuracy. I found a half hour Radio 4 podcast about Emma – I wonder if you know of it? It was a discussion between two academics about her place in history. I found it interesting and it has added to my enjoyment of the book. I do still miss Uhtred made flesh though, not gonna lie.

Hi Lesley. Thank you for telling me about the podcast! I didn’t know of it, and have just now listened to it, enjoying it thoroughly. I will be posting the link on my website, (on March 6, when I put up a post commemorating the anniversary of Emma’s death) and I have you to thank for that. It was interesting to hear the two historians disagreeing on some points — Sue Cameron all gung ho about a really powerful queen, and Vanessa pointing out that she wasn’t all that powerful at first. (Very true.) The issue of how Emma’s marriage to Cnut came about is what intrigued me about Emma right from the start. Was it a negotiation, as she claimed? Or did Cnut have her fetched? I’ve just finished writing the third book in my trilogy, and working out that part of the story took me, literally, months. No one can really know what happened, but I’m awfully pleased with how I’ve interpreted it. I do not, however, describe Cnut as having a stunted, crooked nose. (!!!) It’s too bad that they didn’t have another half hour to discuss Emma, because the events that took place after Cnut’s death, and the rivalry between Emma, Elgiva and their sons are pretty riveting. I’m glad you’re enjoying the book!

I’m so pleased to have been able to pass on the podcast, which I came across completely by chance when doing a bit of digging into Emma’s history. It’s incredible that she isn’t more widely known. Have nearly finished Shadow of the Crown. Thanks for the mention!