Wikimedia Commons

Entry from The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 1052:

Ymma Ælfgifu, King Edward’s and Harthacnut’s mother, passed away.

The very mention of Emma of Normandy’s passing in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is an indication of the significance of her career as queen, queen mother, queen regent and dowager queen, for the Chronicle rarely made mention of women at all. Only the second woman to be crowned queen of all England, Emma was as well the only woman ever to be crowned queen of England twice. For nearly fifty years, through the reigns of seven kings—Æthelred, Swein Forkbeard, Edmund Ironside, Cnut, Harold Harefoot, Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor—she was a significant figure in 11th century English politics.

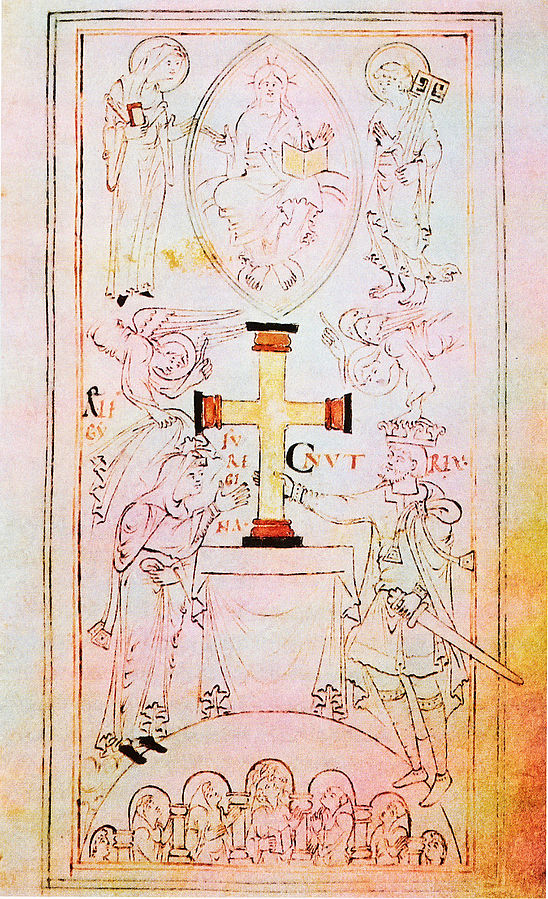

Queen Emma & King Cnut. New Minster Liber Vitae, 1031. British Library, Stowe 944, fol.6. (Wikimedia Commons)

Because Emma’s birth date is unknown, her age at the time of her death is a matter of speculation, although she was certainly in her late sixties. Nor is there any indication of the cause of her death. She had retired from court probably in 1047, and since then had been living quietly in her dower city of Winchester. Had she been ailing during that time? It is impossible to say.

Her great nephew William the Conqueror, who would use his blood connection to Emma to justify his claim to the English throne in 1066, may have spoken with her when he visited England in 1051. Emma’s biographer, Pauline Stafford, speculates that William may have wished to discuss the question of English succession.

If Emma met with him for such a discussion, one fraught with enormous political implications and a crown in the balance, she can hardly be considered as ‘ailing’.

The exact date of Queen Emma’s death was March 6, 1052. She breathed her last in Winchester and was buried in the crypt of the Old Minster beside her second husband King Cnut and their son King Harthacnut.

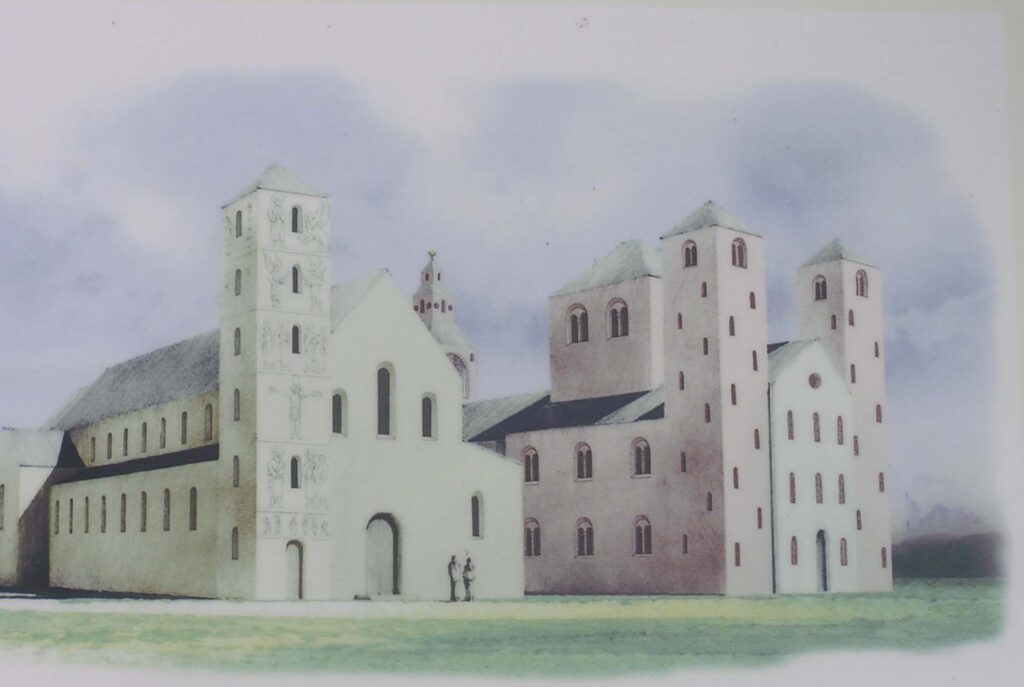

New Minster (left)…Old Minster (right)

Prior to this, queens in England and Wessex had been laid to rest in the abbeys where, frequently, they retired in their widowhood. Emma was the first to be interred in the royal mausoleum at Winchester, and the only woman among the 23 individuals whose bones have recently been removed for examination from the mortuary chests that since Tudor times have rested atop the high stone screens of the chancel.

The mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral.

It is interesting that Emma’s son, King Edward the Confessor, who would presumably have been responsible for her interment, buried his mother not with his father at St. Paul’s in London, but with her second husband and their son in the royal city of Winchester. Perhaps, in doing so, he was fulfilling Emma’s particular request—to lie for eternity beside the king during whose reign she had the greatest influence and prestige.

Painting of Cnut asking for the hand of Queen Emma. Fredericksborg Palace, Denmark.

Interesting stuff about Queen Emma. I will be reading your trilogy on Queen Emma. On this date, 970 years ago she passed.

I realize that historically there’s little said about Emma’s actual relationship with Athelstan, but within the context of your trilogy, I thought it was an interesting little detail to see that Athelstan and Emma were both buried at the cathedral at Old Minister in Winchester.

(I didn’t expect it, but I became attached to that particular relationship from reading your trilogy, maybe in that version of history, Emma had a wish to be near her lost love as well.)

Hi Maggie. I’m pretty fond of that relationship between Emma and Athelstan as well. Yes, that relationship was completely invented by me, but they would have been 15 or 16 years old and I don’t think it’s too far-fetched to think there may have been an attraction between them. (I can remember what it was like to be 15!) And it’s interesting that you bring up the fact that they are both buried at Winchester. The remains that are buried in the mortuary chests at Winchester (they have found that there are 43 people, more than they expected) may well include Athelstan. I wonder if we’ll ever know…